U.S. Ending Term As Chair of Arctic Council – But Must Remain Arctic-Focused

This week, the United States ends its term as Chair of the Arctic Council with a ministerial meeting in Fairbanks, Alaska attended by all eight Foreign Ministers from the Arctic nations. This meeting comes at an important time in the history of the Arctic, as the polar region transitions from an area closed to human use, to one open to exploitation and transit. There is nowhere in

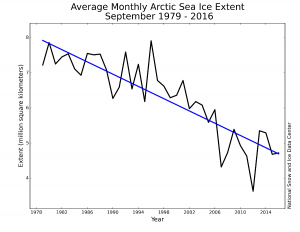

September Sea Ice coverage since 1979

the world warming faster than the Arctic, with temperatures rising twice as fast as the rest of the world – 2016 was 3.5° C warmer than the beginning of the 20th Century, while sea ice cover is falling in a dramatic spiral, with September 2016’s minimum being the second lowest on record.

In late 2014, I testified before the Subcommittee on Eurasia and Emerging Threats of the House Foreign Relations Committee about America’s role in the Arctic. My testimony focused on my concern that the United States had undervalued its role as an Arctic nation and was failing to meet the challenges of an opening Arctic. I expressed concerns that our geopolitical rivals were racing to secure influence in the Arctic while the United States was focused elsewhere.

Once the United States took over the chair of the Arctic Council, however, my fears were eased. Admiral Papp, the former Commandant of the Coast Guard, was named as the Special Representative for the Arctic. The Department of Defense updated its Arctic Strategy, while agencies across the government released strategies detailing action in the region. The Arctic Science Ministerial brought polar scientists from around the world to Washington. President Obama’s 2015 trip to Alaska highlighted the beauty, importance, and fragility of the Arctic. Congress agreed to funding

The US put forward three laudable goals for its Chairmanship: (1) improve living conditions for those living in the Arctic, (2) improving safety, security, and stewardship of the Arctic Ocean, and (3) building resilience to climate change in the Arctic. Although these goals were put forward by the Obama Administration, they have been taken forward by the Trump Administration.

During its chairmanship, spanning two Administrations, the US can point to some significant advances along all three goals. In Fairbanks, the Ministers will sign an “Agreement on Enhancing Arctic Scientific Cooperation,” a legally binding agreement that will facilitate cross-border information sharing and scientific access around the polar region. That builds on two agreements that had already been confirmed, on search and rescue in the Arctic region and responding to oil spills. Beyond these multilateral agreements, there are two new studies that have been initiated: on a new shipping database and an assessment of telecommunications needs for the region.

Now, however, I’m worried that the new Administration will simply go back to ignoring the Arctic while America’s adversaries push forward with their plans to exploit the Arctic’s wealth. To be clear, I would be as concerned about this if a Democrat were in the White House as I am now. Unlike the central role the Arctic plays in Russian or Scandinavian culture, for most Americans, the Arctic is a faraway place about which we know little.

Admiral Robert Peary, 1909

In 1909, Admiral Robert Peary’s expedition became the first to reach the North Pole. In a telegram to then-President Howard Taft, he said “I have the honor to place the North Pole at your disposal.” Taft replied: “Thanks for your interesting and generous offer, I do not know exactly what to do with it.” Unfortunately, American interest in the Arctic may not have changed that much since Taft wrote that message: we still do not know exactly what to do with it.

As the Arctic melts, how countries respond to an opening ocean will determine whether it remains a zone of peace, or becomes an area of conflict. The new Administration, and Americans should not forget that the U.S. is an Arctic nation, with a role to play.