Market Expansion Risk and Global Mobility

Firms are not only scrambling to compete in BRIC countries, they are also looking beyond the horizon for growth in frontier markets in Sub Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and other regions. Despite the inherent risks of expatriation to emerging and developing economies, international assignments are slated to grow 50% by 2020, according to a recent PwC study. This is so because of the dueling interests of talent in frontier markets and the seemingly boundless economic growth rates, which are redefining company strategy and market expansion priorities. This shift is unsurprising, as emerging and developing economies will account for six in seven people on the planet by 2016 and are no longer solely the domain for extractive industries, but are now being treated as pure markets in virtually every sector of the economy. C.K. Prahalad in his seminal work codified the notion that there is a fortune at the base of the pyramid.

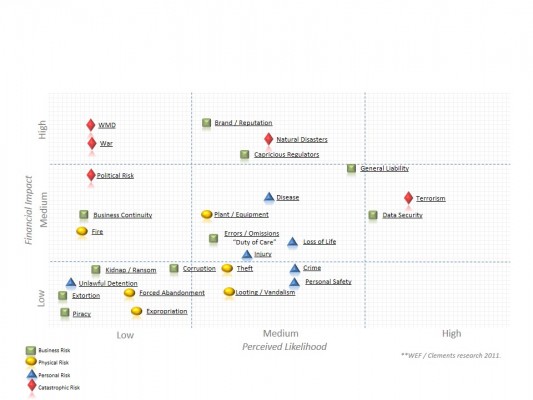

Figure 1 – Risk Matrix: Emerging Economies

Beware the base of the pyramid is rife with risks!

Given the low level of infrastructure development, emergency preparedness, political stability and exposure to acts of nature, the practice of market expansion must forever change in order to adapt to this “new normal.” When comparing the risks faced in advanced and emerging markets, the tone and tenor of risk changes dramatically. Chief concerns that keep risk managers awake at night in advanced markets will seldom displace hundreds, thousands or even millions of people. Besides, communication infrastructure and the knowledge labor force that predominates high value-add activities in advanced markets is such that business continuity is highly likely even in catastrophic scenarios.

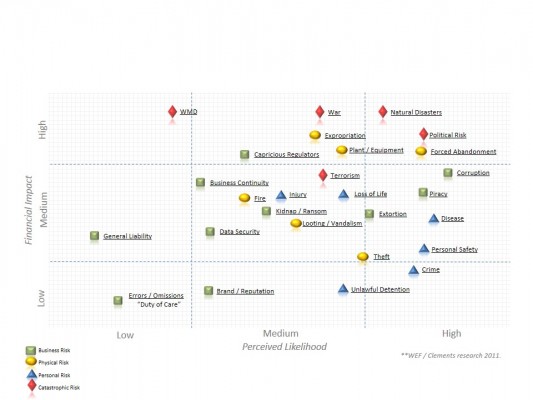

Figure 2 – Risk Matrix: Advanced Economies

The economic impact of catastrophic losses in advanced economies will be quickly abated, as government reconstruction, stimulus funds and insured losses fill the void. Along these lines, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which killed more than 230,000 people, displaced millions and affected 12 countries, caused less than 20 b.USD in insured losses, according to the reinsurer Swiss Re. Contrast this with the Sendai earthquake and tsunami of 2011, which claimed approximately 23,000 lives and caused an estimated 250 b.USD in insured losses. The Japanese automotive industry, whose supply chains, plants and people were severely disrupted following the dreadful trifecta of an earthquake, tsunami and the ensuing nuclear fallout, have quickly regained their footing and are operating at pre-calamity levels. In a developing or emerging market context, however, the risk picture changes dramatically.

Firms and market expansion choices are exposed to a new array of challenges, where such a mundane activity as driving down the road is one of the leading causes of death and injury. Corruption, bribery and fraud are often the bywords of doing business in many countries and are as pervasive as taxation in advanced markets. So, too, are the ascendant risks of piracy, unlawful detention, creeping expropriation and myriad catchy terms that risk managers are adept at handling when it comes to insurance placement and protecting the P&L, but fail to manage at the individual level. The after effect on international assignments brought about by this risk landscape has exposed cracks in the mobility edifice, which is typically comprised of fulfilling the 5 R’s (Recruiting, Relocating, Rewarding, Retaining and Returning).

The need for hard and soft power

Traditionally an adjunct to Human Resources, the global mobility profession is dominated by crucially important tasks, such as assimilation, language training, benefits packages and the general transaction of relocating employees to international posts. This begs the question, how many mobility practitioners can look the CFO in the eyes or are even on the same floor and can challenge the company’s threshold for dealing with a turbulent market? The P&L is carefully looked after and there are countless risk management solutions readily applied by global firms to prevent and dissipate financial losses. However, many of the “people behind the P&L” in expatriate assignments are entirely exposed. Who, for example, is liable for an expat’s personal property left behind because of the effects of the Arab Spring? Abandoned property is typically excluded from insurance policies.

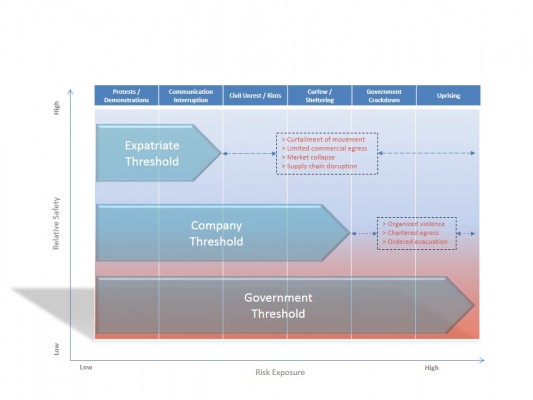

Figure 3 – Risk Tolerance

How is duty of care extended to include the issuance of or access to a company car in emerging or developing markets, which account for 85% of all road traffic deaths and injuries? In fact, unchecked, the World Health Organization forecasts show that road crashes will be the third most common cause of premature death by 2020. How many mobility practitioners arrange “drive to survive” courses for their international assignees? Whether the practice of balancing soft power with hard power is prevalent today is irrelevant. What matters is the pace of adaptation in the mobility discipline to the dynamic changes unfolding in the emerging world and the dichotomy of sending the best talent to often risky environments in the pursuit of growth.

In order to oversee this shift and better understand the growing trends affecting expatriation in developing markets, firms must elevate the role of the mobility practitioner to a c-suite executive responsible for all facets of internationally mobile human capital. Contrasted to the current practice, which tends to be transactional in nature, several layers removed from the top and focused on so called “soft” elements, the Chief Mobility Officer will be a peer to other executives and reports directly to the CEO, from whom they are conferred firm-wide oversight and accountability. Strategic in nature, the CMO’s priorities are the fulfillment of company strategy through the deployment and ongoing management of expatriates to the four corners of the world. Firms that adopt this role will gain an edge in competing for the great rewards in emerging markets, while mitigating the many risks of operating in the world’s frontiers.

[…] Market Risk and Global Mobility […]