Military Engagement on Climate Strengthens Ties in Asia

Last weekend, senior leaders from across Asia and the Pacific gathered in Singapore for the IISS Shangri-la Security Dialogue. It looks like there was some fireworks, according to my old boss, Nigel Inkster, who said “The gloves came off.”

In this time of heightened tensions, there is an area where countries and militaries can work together. Humanitarian assistance and cooperation can build relationships between the U.S. and countries across Asia. Much of that cooperation will come around preparedness for climate change.

Planning for climate change is important in the Pacific area of operations because it will fundamentally alter the operating environment in ways which will cause harm to the national security of countries around and within the Pacific. However, planning for climate change in the region is also important because the other countries in the region perceive it as important. As Dale Carnegie says in How to Win Friends and Influence People: “To be interesting, be interested.” In other words, in order for the U.S. to gain influence in the Pacific, the U.S. must be interested in what countries in the region are: and the threats posed by climate change interest them deeply, as ASP’s Global Security Index on Climate Change shows.

The area around the Pacific is perhaps the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change because of how multiple threats overlap one another, as our Climate Security Report notes. Environmental factors like rising sea levels, declining fresh water availability, declining food productivity, and the threat of more powerful tropical storms are combining with other factors like rapid urbanization in low-lying river-delta cities, deforestation of tropical forests, and international competition over access to energy resources.

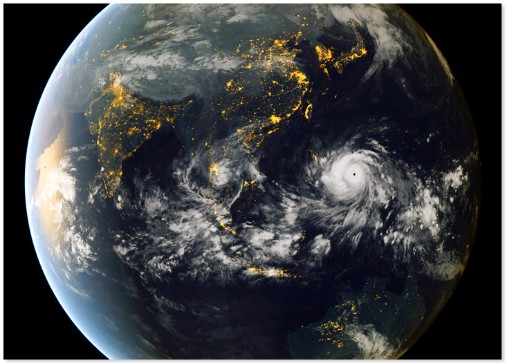

Throughout the fall of 2013, favorable atmospheric conditions combined with abnormally warm water in the deep Central Pacific to spawn five ‘super-typhoons’ with sustained winds greater than 150 mph.

This spate of storms included Super-Typhoon Haiyan, the storm that made landfall in the Philippines with maximum sustained winds estimated at 195 mph – the highest in recorded history to make landfall anywhere in the world. Bryan Norcross, the Senior Hurricane Specialist from the Weather Channel called it “the most perfect storm he’s ever seen.”

Where the storm first hit land, on the east coast of the Philippines’ Samar Island, towering waves on top of a massive storm surge crashed against the coast, creating high water marks 46 feet above mean sea level; the highest level recorded from a tropical cyclone in at least a century.

The result was that more than 7,000 people died around Tacloban, making this the deadliest Typhoon in Philippine history. Filipinos are accustomed to Typhoons – they make landfall nearly every year; the country’s government institutions and its culture are prepared to weather the storms. Haiyan simply overwhelmed their ability to cope; this Typhoon was of a strength unprecedented in human history – how could they have prepared for this?

When a disaster of that scale happens, the US Navy and Marines are the only organization in the Pacific with the logistical capabilities to respond in time in a large enough force to make a difference. Shortly after the storm, Secretary Hagel ordered the USS George Washington’s battle group, then on a port visit to Hong Kong, ”to make best speed” to respond to the Typhoon. In all, over 13,000 Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines were engaged in the Humanitarian Assistance/ Disaster Response (HA/DR in military acronyms) mission to the Philippines.

That response certainly saved lives: even weeks after the Typhoon, doctors, transported to remote areas by Navy and Marine helicopters, were treating patients hurt in the storm. Moreover, these HA/DR missions provide more than simply food, fresh water, and supplies; they can prevent a downfall into lawlessness. In the days immediately after the storm, there were reports of radical Filipino insurgents hijacking aid supplies from Filipino government convoys. U.S. Marines are a harder target – and their presence helped to quell such violence before it became common.

American Engagement on Climate Security Increases Influence

Immediately after the storm, the Filipino Climate Change Ambassador, Yeb Sano, made an impassioned speech to the global negotiators assembled in Warsaw for the round of UN negotiations leading to a successor to the Kyoto Protocol. In a tearful address, he said “What my country is going through as a result of this extreme climate event is madness.” If the United States military had not responded in the way it did, and it the U.S. leadership in the Pacific had actively denied the link between climate change and security, it is easy to see how there could have been a backlash against American interests in the region.

Instead, in April 2014, President Obama visited Manila to sign a new U.S.-Philippines defense pact. Certainly, most of the thrust driving that treaty forward was the rise of China, particularly their aggressive actions in the South China Sea. Nonetheless, the quick American response after Typhoon Haiyan served to remind the Filipino government and people (who have not always supported American military engagement) why it is important to have the U.S. Navy on your side.

U.S. military engagement on this issues is important because prepares for the next storm and it boosts American “soft power” in a region that too often only sees the U.S. through its military perspective. The fact that U.S. Pacific Command and the Department of Defense are preparing for climate change can help to align American interests with the other nations in the region that view climate change as a clear threat to their security.

To underline the importance of climate preparedness to this agreement, the first joint U.S. – Philippine exercises since the pact was signed – the Balikatan war games, held in early May – included a HA/DR exercise to Tacloban City, the very city which had been devastated by Typhoon Haiyan.

[…] Haiyan in the Philippines or the recent Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu? Or how climate aid could actually build support among allies in the region. To me, it seems that is something the Pacific Command should study, not […]

[…] Military Engagement on Climate Strengthens Ties in Asia […]