India and China: Drifting Towards Danger

As tensions rise between the U.S. and North Korea, another conflict between two nuclear-armed countries is flying under the radar. Since late June, relations between China and India have deteriorated over a border dispute. As with North Korea and the U.S., this new dispute doesn’t appear to be cooling down anytime soon.

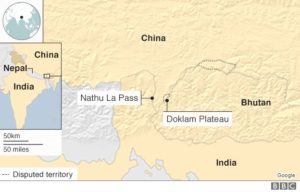

The dispute is over a section of land (the Doklam Plateau) which makes up an unmarked border between China and Bhutan. While not in India, the plateau is close to the small section of land in India (the “Chicken’s Neck”) that connects northeastern India to the rest of the country. Due to concerns about China, India and Bhutan have long had a “treaty of friendship,” with Indian troops based by the Bhutan-China border. India and China fought a war over this border in the 1960s and have seen occasional skirmishes since then. Most recently, China started expanding a road in the disputed Plateau, causing Indian border guards in Bhutan to step in to halt construction. The episode lead to a significant deterioration of relations and there are concerns that any additional stress could lead to a full-blown war. One possible trigger could be water.

The dispute is over a section of land (the Doklam Plateau) which makes up an unmarked border between China and Bhutan. While not in India, the plateau is close to the small section of land in India (the “Chicken’s Neck”) that connects northeastern India to the rest of the country. Due to concerns about China, India and Bhutan have long had a “treaty of friendship,” with Indian troops based by the Bhutan-China border. India and China fought a war over this border in the 1960s and have seen occasional skirmishes since then. Most recently, China started expanding a road in the disputed Plateau, causing Indian border guards in Bhutan to step in to halt construction. The episode lead to a significant deterioration of relations and there are concerns that any additional stress could lead to a full-blown war. One possible trigger could be water.

Climate change is already having a disproportionate impact on both China and India, leading to increased domestic stress. In India, extreme droughts, floods and resulting crop failure has led to a surge in rural to urban migration. With the population exploding, conditions aren’t likely to improve. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that by 2025 India will face generalized water crisis.

China is seeing similar problems with a temperature increase of over 1.1 degrees Celsius since the beginning of the 1900s and a significant increase in extreme weather events. Already, more than half of Chinese cities are considered water scarce as rivers are over-utilized and ground water sources become increasingly polluted. As their population continues to grow and drying trends expand across the country, similar domestic migrations and tension are likely to arise.

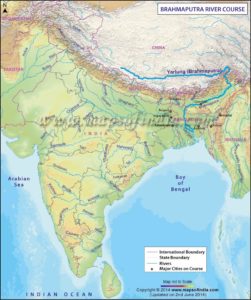

Compounding these threats, the two countries share many of the water sources that will likely become less viable in coming years. Specifically, the countries both rely heavily on the transboundary Brahmaputra River. The Brahmaputra originates in Tibet (where it is called the Yarlung Zangbo) but eventually flows down through the Himalayas across India’s eastern provinces, accounting for nearly 30% of India’s total water resources. This leaves India incredibly vulnerable to any decline in water flow, especially during the dry season. At the same time, China’s growing population and industrial activity is straining water supplies. Tensions already exist between the two countries over China’s increase in dam building in Tibet and possible diversion plans.

Compounding these threats, the two countries share many of the water sources that will likely become less viable in coming years. Specifically, the countries both rely heavily on the transboundary Brahmaputra River. The Brahmaputra originates in Tibet (where it is called the Yarlung Zangbo) but eventually flows down through the Himalayas across India’s eastern provinces, accounting for nearly 30% of India’s total water resources. This leaves India incredibly vulnerable to any decline in water flow, especially during the dry season. At the same time, China’s growing population and industrial activity is straining water supplies. Tensions already exist between the two countries over China’s increase in dam building in Tibet and possible diversion plans.

While climate change wouldn’t be the cause of a war between these two countries, there is reason to worry about future skirmishes over water. Increased water and social tensions at home, combined with the pre-existing tension between the two countries could lead to a conflict. All of this is made more likely by the increasingly nationalistic rhetoric coming from both countries. Indian Prime Minister Modi’s party, known for its stringent policies toward China, recently won a number of seats, and China is unlikely to back away from their nationalistic stance with growing antagonism from the south.

Hopefully, this current dispute can be resolved diplomatically. In the longer term, the countries should build confidence about cross-border water supplies and work together on shared challenges. A similar treaty to the India-Pakistan Indus Water Treaty would be a good start. By building confidence now, there’s a chance to reduce the likelihood of future escalations leading to a war between these two large, nuclear-armed countries.