Building Caribbean Resilience with Fossil Fuel Revenues

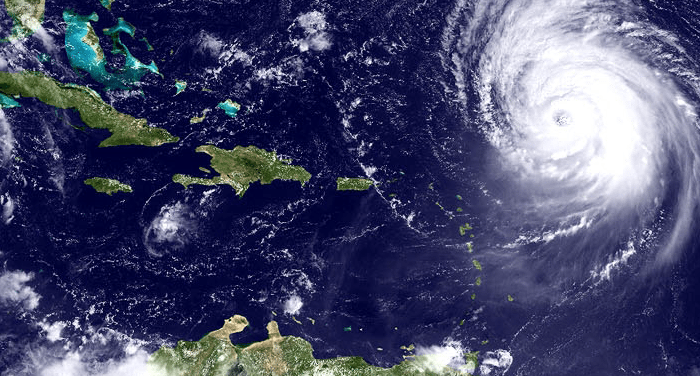

In September 2017, Hurricane Maria carved a swath of destruction across the Caribbean, leveling the islands of Dominica and St. Croix, before taking direct aim at Puerto Rico. Most of the island was without power for months, as the electricity grid was destroyed. Only 2 weeks earlier, Irma had left a similar trail of devastation: first leveling the small islands of Barbuda and others in the leeward islands, before tracking to Cuba, the Florida Keys, and up the Gulf Coast of Florida. The National Hurricane Center estimates that Maria and Irma were the third and fourth costliest Atlantic Hurricanes in history, causing over $160 billion in damage. Hundreds of people people died in the storms, and then nearly 3,000 died in the months that followed due to the failed recovery. Only Harvey’s extreme rains and flooding in the Houston area, also in 2017, and Katrina in 2005 were more costly storms.

These Category 5 storms should have been a clear warning to Americans and the Caribbean that the old, ad-hoc way of hurricane response and rebuilding for the Caribbean was no longer sustainable. As climate change grows worse, they are a harbinger of the storms to come in a warmer, more dangerous world. The Caribbean is one of the most vulnerable places in the world to the effects of climate change. While its warm waters draw tourists to idyllic beaches, they also spawn some of the most dangerous storms in the world, and climate change is making those waters warmer, enabling storms to grow larger and more dangerous. While scientists are unclear about climate change’s impact on the number of hurricanes, there is clear scientific consensus that warmer waters make storms more powerful. Moreover, sea level rise, driven by ice melt and warming, is also increasing the damage those storms can cause, causing storm surges above already higher water levels.

At the time, writers and commentators noted how the storm season of 2017 would prove a wake-up call to those living in the Caribbean and those that care about it. Unfortunately, as the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season begins, its clear that the lessons from 2017 haven’t been learned well-enough. As an ASP article published immediately after Hurricane Maria showed, there are generally understood to be three phases to a disaster response: Relief, Recovery, and Rebuilding – but there should be a fourth as well: Resilience. Resilient infrastructure and housing would ensure that each of the three stages went faster because less damage would be done initially. After the storms, a common refrain was the need to “Build Back Better.”

For too much of the Caribbean, the only reminder of the storms of 2017 is ruined homes, failing infrastructure, and unkept promises. Since 2017, few new policies have been put in place across the Caribbean to build the resilience necessary to protect from storms. While the Caribbean is a diverse array of countries with different cultures, speaking different languages, and of different sizes, they all are vulnerable to extreme weather.

They have attempted to build unified efforts to protect the region from storms; hurricanes are not new to the Caribbean, after all. There is an existing intergovernmental infrastructure intended to share risk and decrease the fiscal burden of storms across Caribbean states. The Caribbean Catastrophic Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF) was created in 2007 as a way to pool risk among member countries in the Caribbean basin. It provides recovery funding to areas hit by extreme disaster, and is intended to help in the recovery and rebuilding phase after a disaster. Even older, the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) is the unified intergovernmental agency for disaster management of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), which focuses on immediate disaster response.

However, like too much throughout the history of Caribbean states, these good ideas are beset by a lack of capital and capacity. To build real, long term resilience in a poor, economically disadvantaged, geographically challenging region, significant capital expenditures will be needed.

Dedicate Fossil Fuel Revenues to Disaster Response

Ironically, as the Caribbean is becoming a global hotspot for disasters, it is also becoming a new center for fossil fuel production. Guyana, which hosts the CARICOM secretariat, has started shipping oil from its offshore reserves, and will become one of the largest producers of oil in the Western Hemisphere. Trinidad and Tobago have been the center of petroleum production for decades, with a thriving natural gas export market. Other islands are poised to grow as well. Finally, just north of the Caribbean basin, deep offshore oil production in American waters in the Gulf of Mexico continues to provide significant revenue and production.

Although environmental campaigners make a valid argument to “leave it in the ground,” there are few governments willing to forgo the revenues of oil production. To give up resource that can build prosperity for their country is not a pathway towards political survival. So long as the global economy demands petroleum, countries with oil resources (whether you see it as a blessing or a curse) should instead find ways to build long-term prosperity with oil revenues.

In the Caribbean, policymakers should directly dedicate revenues from fossil fuels to build the resilience that would protect the region from the most dire impacts. The CCRIF and CDEMA could be fortified with revenues dedicated from fossil fuels. But this shouldn’t be solely Caribbean Basin countries funding their own resilience. The United States, Canada, and European countries have long-standing ties, interests, and historical responsibility for supporting sustainable development in the Caribbean. These developed countries, after all, are responsible for the majority of the greenhouse gas emissions that are super-charging hurricanes and extreme weather.

As a new initiative of a new Administration, the United States should lead the way. The American government should pledge to dedicate the revenues from oil production in the Gulf of Mexico to providing resilience funding to coastal communities at risk in the Americas (over $6 billion in 2019). This funding can be split between communities on mainland U.S., in heavily impacted Puerto Rico, and as aid to Caribbean countries and intergovernmental institutions like the CCRIF and CDEMA.

To mark this new commitment in 2021, as the next hurricane season is beginning, the United States should call together a meeting of leaders from the region to announce and publicize the new initiative. There would be few better ways to show how the United States was returning to the Caribbean and to building closer relationships in the Western Hemisphere.

In 2015, then-Vice President Biden hosted the Caribbean Energy Security Summit in Washington to highlight the importance of building comprehensive energy security in the Caribbean basin. That program has been successful in reducing Caribbean energy dependence. Next year, should work to use the growing energy revenues to build the resilience and long-term economic base that these countries need. If countries are going to profit from fossil fuel exploitation, they should at least use the funds to “fix their roof while the sun is shining.”