The Blue Nile. Image c/o wo de shijie (Flickr). License: https://bit.ly/3jYe4bz.

The Blue Nile. Image c/o wo de shijie (Flickr). License: https://bit.ly/3jYe4bz.

The Ebbs and Flows of the Renaissance Dam Dispute

The American Security Project (ASP) has long followed the protracted dispute over Ethiopia’s Renaissance Dam. In March, ASP wrote about the conflict’s role as a harbinger of things to come in a drier world. This piece followed a series of articles and reports covering various aspects of the Ethiopia-Egypt-Sudan clash, from Nile power politics to the global security implications of interstate dam disputes.

Today, the conflict over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) shows no signs of abating. It is instead growing worse, demonstrating just how intractable water security issues can be—especially as climate change further depletes resources. By delving further into the past and future of the GERD, we can better prepare ourselves for future conflicts over water that are sure to come.

CONFLICT BACKGROUND

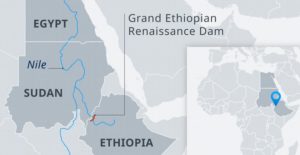

Ethiopia began construction of the dam in 2011, making the current dispute almost a decade old. At the cost of $4.5 billion, the GERD will be the largest hydropower dam in Africa once completed. It spans the width of the Blue Nile—the main tributary of the Nile River beginning in the Ethiopian highlands (see map, below).

Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. CC image c/o Sheetal Sinha on Wikimedia Commons; license here: https://bit.ly/2D7lF6T.

For Ethiopia, the dam is all about power. An estimated 65 million Ethiopian citizens currently lack access to electricity; Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed plans to use the GERD to generate some desperately-needed voltage. An added perk is that once operational, the dam will provide excess power Ethiopia can sell to its neighbors. To start power generation, however, Ethiopia must divert 4.9 billion cubic meters of water from the Blue Nile to fill the GERD’s reservoir—an amount representing approximately 10% of the tributary’s average annual flow. The ultimate plan is for the dam’s reservoir to hold over 74 billion cubic meters of water, giving Ethiopia even greater control over the Blue Nile.

This plan does not sit well with Ethiopia’s two downstream neighbors, Egypt and Sudan, which rely on the Nile almost exclusively for fresh water. Egypt is most fiercely opposed and has accused Ethiopia of violating a 1959 treaty that guarantees a certain annual amount of the Nile’s water to Egypt. Ethiopia, however, insists the colonial-era treaty sidelined its concerns and ignored its sovereignty. Sudan, both figuratively and literally, is caught in the middle. It shares Egypt’s concerns about water supply and the potential for catastrophic flooding should the GERD fail, but it also stands to gain from greater electricity generation.

Trilateral talks among Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan have continued on and off since 2011. Punctuated by intermittent Egyptian threats of war, these discussions have yet to arrive at a resolution agreeable to all. In November 2019, the World Bank and the U.S. Treasury Department spearheaded the latest attempt at diplomatic negotiations—which fell apart earlier this year due to disagreement over the rate at which Ethiopia should fill the GERD’s reservoir.

CONFLICT UPDATE

In early July, tensions flared when satellite photos appeared to show Ethiopia unilaterally filling the reservoir. Ethiopia has claimed the water is due to seasonal rainfall, but its longstanding insistence it does not need permission to fill the reservoir complicates this assertion. So, too, does the sheer amount of water behind the dam (see photo, below).

First filling of the GERD. CC image c/o Hailefida on Wikimedia Commons; license here: https://bit.ly/2EDmkgY.

Egypt reacted immediately, with President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi refusing to rule out military action. The threat of war speaks to the role nationalism plays in the conflict over the GERD. Egypt has historically adopted a highly nationalistic stance on the Nile River, relying on twentieth-century agreements with Britain to claim a right to Nile waters. The GERD, however, has emerged as a symbol of Ethiopian national pride—and Prime Minister Ahmed is unlikely to compromise on one of the only things unifying Ethiopians at a moment of severe ethnic strife in the country.

The danger of immediate conflict seemed to recede on July 21, when Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan agreed to resume talks under the aegis of the African Union. On July 27—the first day of the new talks—Egypt and Sudan criticized Ethiopia for unilaterally filling the reservoir. Although not an auspicious start to the new round of negotiations, there is still cause for cautious optimism. Historically, tension over shared bodies of water has led to more cooperation than conflict. An equitable water-sharing agreement will help put the GERD on the right side of history.

WHY IT MATTERS

The accelerating pace of climate change makes it even more imperative for Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan to agree. Over the next century, climatic warming will drastically alter water dynamics in the Nile Basin: researchers predict water demand will outstrip supply by 2030. Since it will take approximately seven years to fill the GERD’s reservoir, the completion of the dam will converge with this water shortage—exacerbating tensions unless there is a legal framework for action.

Absent an international agreement, the future of the GERD could very well mirror that of China’s Three Gorges Dam. Controversy plagued the construction of the Three Gorges, which China completed in 2006. The main issues included: the danger of dam collapse, the displacement of approximately 1.4 million people, and fears of reservoir pollution from industrial waste. In 2011, Chinese officials admitted the dam’s adverse effects on downstream regions. In mid-July, the Three Gorges reappeared in headlines as unprecedented floods in China raised the specter of a catastrophic dam collapse.

Nor do China’s ambitions end with Three Gorges. President Xi Jinping has expanded control over the Mekong River—a lifeline for the countries of Southeast Asia—through a series of hydroelectric dams and channel alterations to make way for larger ships. By providing a blueprint for international governance of shared waters, an Ethiopia-Egypt-Sudan agreement on the GERD would promote hydro-solidarity over hydro-hegemony.

HOW THE U.S. CAN HELP

The dissolution of the Trump-mediated talks earlier this year reveals the limits of U.S. involvement in the GERD dispute. These talks possessed two fatal flaws: Ethiopia believed the U.S. to be a biased mediator, and the Treasury Department sidelined the State Department. There are no short-term fixes to either problem, so the U.S. should take a backseat for now and allow the African Union to continue leading negotiations.

In the long-run, however, the U.S. must address these issues. First, Ethiopia does not trust American mediation because of perceived favoritism toward Egypt. A close U.S. partnership with Egypt informs this belief—for example, America has provided Egypt $1.3 billion in annual military assistance since 1987. To overcome this perception, the U.S. should focus on strengthening diplomatic and financial ties with African states beyond Egypt. Trump’s recent threat to cut Ethiopian aid if the GERD impasse continues is entirely the wrong move.

Second, the State Department typically handles such sensitive diplomatic issues. The next administration must re-empower State to fulfill its traditional role in international negotiations, while also modernizing the department for the landscape of diplomacy in the twenty-first century. By reinvigorating its soft power, the U.S. can position itself to play a greater role in resolving the next water dispute—a dispute climate change makes all but inevitable.