Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard.

Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard.

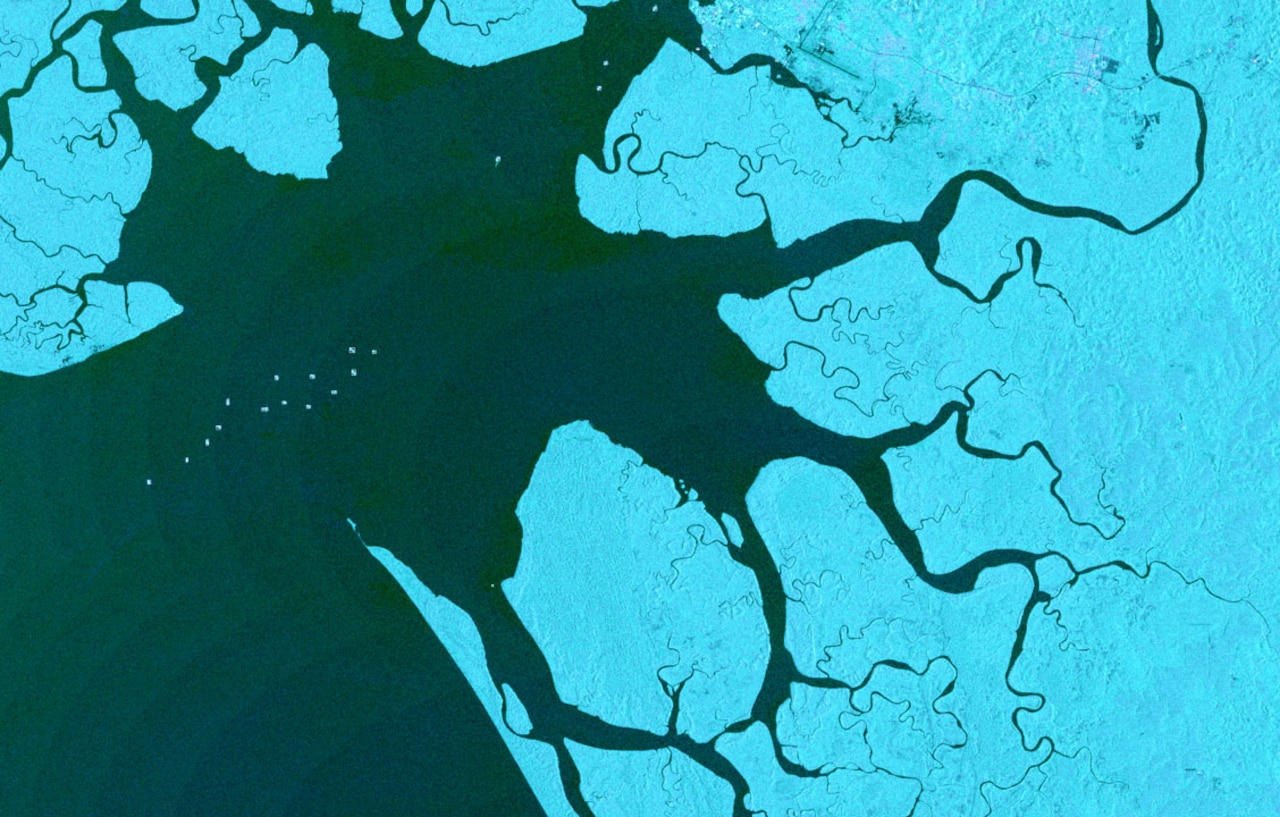

Monitoring Technology in the Fight Against IUU Fishing

Effectively combatting illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing practices requires far-reaching enforcement tools and comprehensive intelligence gathering. Monitoring vessels for illegally fished species, bycatch, human trafficking, and other transnational crimes ensures the sustainability of our oceans and brings justice against illegal fishers who continually evade detection.

Due to the immense surface area of the ocean seascape, instances of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing are challenging to track and deter consistently. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) enacted in 1982, coastal nations are required to manage and police marine resources within their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). EEZs extend a coastal States’ maritime jurisdiction up to 200 miles offshore—beyond the EEZ lies the high seas. The only form of regulation over the high seas exists through Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), which are international commissions tasked with protecting certain fish stocks or ecosystems.

Maritime authorities within EEZs and on the high seas often fail to detect IUU fishing violations without proper technological and administrative resources. A lack of coast guard presence and intelligence as to IUU fishing hotspots leaves fish stocks vulnerable to IUU fishers, particularly along the coastlines of developing countries. Realistically, conducting a constant physical police presence for IUU fishing violations is infeasible; thus, implementing efficient surveillance technologies is crucial to monitoring vessel activity consistently.

MONITORING CONTROL SURVEILLANCE (MCS) CAPABILITIES

The current vessel tracking technologies utilized for policing vessel activity on the high seas are the Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS) and Automatic Identification Systems (AIS).

Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS) are satellite-based surveillance systems used to monitor the location and movements of vessels within a States’ EEZ. This technology transmits position reports from onboard transceiver units that certain ships must carry. The position reports are shared with the proper authorities and include vessel identification, time, date, and location.

Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) also transmit vessel location information. However, it does so at increased rates through very high frequency (VHF) radio signals accessible to more than one data collection endpoint. Unlike VMS, AIS technology broadens access to AIS information to more than one receiver. While initially developed to prevent ship collisions at sea, this technology is now employed to detect IUU fishing activity. Increased accessibility to data on IUU fishing activity encourages efficient interagency and organizational collaboration and creates more comprehensive monitoring practices against bad actors.

Where VMS records a ship’s position as little as once per hour, AIS devices share their position every few seconds. This increased transmission frequency better equips authorities to detect “transshipments.” Transshipment at sea occurs when fishing boats and refrigerated cargo ships transfer supplies from one ship to another. Transshipment at sea provides an opportunity for vessels to evade authorities and engage in illegal activities such as co-mingling catch, drug smuggling, weapons and human trafficking, and refueling to avoid detection.

GAPS IN ENFORCEMENT

Unfortunately, ambiguities exist in VMS and AIS monitoring systems that allow IUU fishing violators to continue undetected and unpunished. Alyssa Withrow, American Security Project’s IUU Fishing Research Associate and author of Bad Catch: Examining Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing, explained, “Vessel operators can turn off both the automatic identification system (AIS) and vessel monitoring system (VMS), allowing the vessel to go ‘dark’ for hours to days at a time.”

Gaps in legislative requirements exist as well. Today, the U.S. only requires large boats (longer than 65 feet, from stern to bow) to implement AIS, a figure comprising only 12.4% of the U.S. fishing fleet. Furthermore, these vessels are only required to have AIS turned on within 12 nautical miles of shore, an area covering less than 8% of the U.S. EEZ. In delineating exactly where state enforcement personnel are willing to police for IUU fishing violations, these regulations encourage IUU fishing activity beyond the specific scope defined by statute. IUU fishers know they can conduct illegal activities in areas where vessel location transmissions are not legally required and circumvent state oversight by employing smaller vessel fleets.

SOLUTIONS

To help combat IUU fishing practices and related forced labor abuses in the seafood supply chain, Reps. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.) and Garret Graves (R-La.) introduced the Illegal Fishing and Forced Labor Prevention Act. This bill would expand the requirements for boats to broadcast AIS beyond U.S. national waters and encompass a broader category of boats to implement this technology—both essential steps towards comprehensive IUU vessel detection and deterrence.

Beyond government, several private organizations have made advancements in technology for IUU vessel detection. Global Fishing Watch (GFW) has created the first open-access database of global fishing activity, updating vessel locations near-real-time on the high seas. To develop this technology, Global Fishing Watch partnered with: Oceana, an ocean-focused environmental non-profit; SkyTruth, a technology non-profit utilizing satellite imagery and remote sensing data for environmental protection; and Google, providing Cloud Platform access for big data processing. GFW’s carrier vessel portal allows GFW and other groups policing maritime jurisdictions to plot transshipment hotspots over time, helping to predict where IUU fishing violations are likely to occur next. Open-sourced data compilations like GFW’s can also detect suspected IUU fishing vessels engaged in forced labor and human trafficking. It does so providing researchers with access to data that includes tracking a vessel’s time at sea, documenting gaps in AIS transmission, and recording the number of hours spent fishing per day.

The Environmental Defense Fund’s Smart Boat Initiative is an effort toward implementing artificial intelligence (AI) record-keeping and vessel-counting technology in small remote fishing industries. Their six pilot programs, operating from Indonesia to the California coast, are working to reduce costs for electronic monitoring, improve efficiency in data collection and species sorting, and automate other onboard compliance systems. Harnessing AI technology to expedite catch reporting and data processing streamlines vessel compliance to prevent IUU fishing. Smart Boat Initiative provides access to monitoring technologies that are often difficult to implement for small-scale fishing vessels operations due to lack of resources.

The Department of Defense currently runs a cooperative program with GFW that enlists private tech companies in the U.S. to develop innovative tools for detecting IUU fishing on the high seas. The xView3 Challenge is a competition awarding a $150,000 cash prize to the participating individual or company that develops the best performing algorithm for identifying and classifying synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite imagery of suspected IUU fishing vessels.

Policing the world’s vast and complex ocean ecosystem is nearly impossible without efficient monitoring technology. Partnerships between the tech industry, fishing companies, and governments can encourage streamlined solutions to bolster maritime security. Implementing state-of-the-art monitoring equipment like AIS and VMS on vessels worldwide is vital to holding bad actors accountable for engaging in IUU fishing activity. Regardless of size or registration status, legislation should require monitoring devices such as VMS or AIS on all ships. Ensuring the longevity of global fish stocks requires participation and transparency from all parties fishing our oceans. Accounting for all vessels will create the most precise data set possible, informing state policymakers in shaping more innovative and adaptable regulations for sustainable fishing into the future.