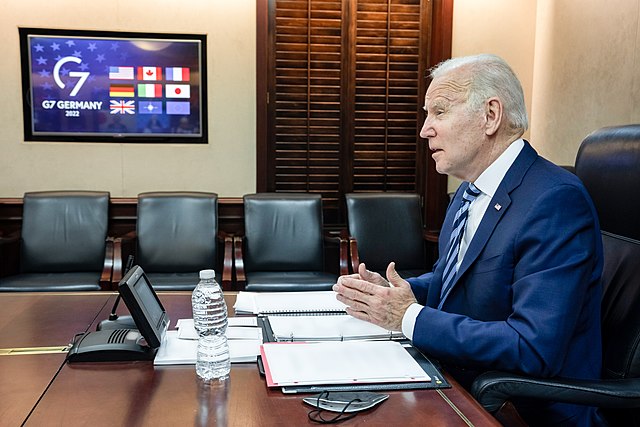

Biden Announcing Sanctions on Russia | Photo Credit: The Biden White House

Biden Announcing Sanctions on Russia | Photo Credit: The Biden White House

Analyzing Russia’s Economic Resiliency

Shortly after Russia sent its troops to the separatist territories of Donetsk and Luhansk, both Europe and the U.S. implemented new and broad sanctions on the Russian government. Such sanctions underscore the condemnation of Russia’s actions, though David Leonhart of the New York Times warned that sanctions don’t often work unless they’re harsh enough to cause societal pain. However, President Putin has pursued a plan some analysts dubbed “Fortress Russia,” which included buying gold reserves and increasing exports to China in order to increase Russia’s economic resiliency. Russia’s policies amount to having stacked economic sandbags to withstand some of the pressure in the short term, but a robust list of sanctions can potentially force Russia to seek a more favorable agreement for Ukraine.

Previous sanctions had some bite as Russian firms found it harder to do business after the annexation of Crimea. Combined with the decline of oil prices in late 2014, Russia’s GDP declined dramatically from $2.3 trillion in 2013 to $1.4 trillion in 2015. Since then, however, Russia took steps to minimize its exposure to the U.S. dollar and to foreign creditors. Russia has also pursued a tight fiscal policy restricting its debt to GDP ratio to around 20 percent. Putin also increased Russia’s gold and foreign exchange reserves to an all-time high of $630 billion as of December 2021, though up to 40 percent of reserves are located outside of Russia. Lastly, there has been an import substitution drive to improve domestic production in agriculture and pharmaceuticals, as well as a pivot to make China Russia’s new largest trading partner. Just this month, China signed an agreement to buy Russian natural gas for Euros (thus bypassing sanctions involving the U.S.). These actions ensure that the Russian can remain standing for the short-term.

Russia is ready for the economic consequences though it still has vulnerabilities seen within the first day of the war. Currently, Russia is still exposed to the U.S. dollar as over 56 percent of all exports are denominated in dollars, though it is a smaller share than in 2014. The private sector is still dependent on the dollar for everyday foreign exchange transactions. It is also dependent on SWIFT, the main system for global financial transactions messaging and notifications, from which select Russian banks have already been expelled. Russia is also dependent on the global chip industry and now that Europe and the U.S. are commencing export bans, the technology sector will be crippled as Russia has few alternatives for acquiring these chips. With the invasion of Ukraine, such vulnerabilities can now be exploited by NATO as they seek to punish Russia for its aggression.

Putin has already thrown away his upper hand as his actions united NATO against Russia and possibly started a groundswell of activism against him. Now, the U.S. and Europe should use sanctions that can harm the Russian economy, even if it will cause reverberations to the West. Michael S. Billingslea, currently a fellow at the Hudson Institute, tweeted that sanctions on the whole financial sector, the Russian elite, and on the Russian Central Bank, would bring the Russian economy “to a screeching halt.” While the West has so far acted on much of what Billingslea recommended, there are no sanctions on the Russian oil and gas industry, whose largest customer remains the European Union. The Biden administration did announce the release of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, but while such releases are able to ease some of the sticker shock for consumers in the U.S. and Europe, they are insufficient to absorb the severe impact a ban on Russian exports would cause to the global energy market. Right now, everyday Russians are starting to feel the effects of an increasingly isolated economy, but if sanctions avoid the energy sector, it could provide Russia with essential capital that can at least sustain the government and the elites.

In the short term, Russia’s low sovereign debt and high foreign reserves will allow the government to continue financing its operations and military invasion. But now that many states are involved in implementing sanctions, including countries with a historic policy towards neutrality, such sanctions can take a harder grip on Russia than previous efforts. If these sanctions are expanded to the energy sector, it could ideally lead to greater internal dissent against Putin. Even with improved ties with China, Russia’s economic ties with Europe cannot be easily substituted eventually whittling down the economic fortress it spent years building. Putin is already facing anti-war demonstrations and his military advances are not going as well as anticipated—further economic sanctions that paralyze the Russian economy could turn the tables against him once and for all.