GUEST POST – A New Agreement on HFCs

Authored by Lt. General Norman Seip, USAF (ret.)

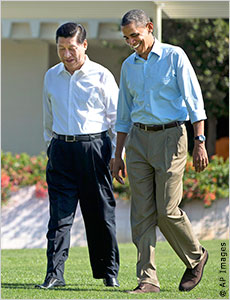

In a highly anticipated meeting this past weekend, President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping discussed a series of important issues in the bilateral relationship, ranging from North Korea to cyber security, maritime borders to trade.

One issue that was overlooked by much of the media accounts of the event was an agreement on climate change. The two nations agreed to decrease the production and consumption of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). This could be a major step between the globe’s two largest emitters of greenhouse gases. The agreement, if implemented, will have significant effects on both the climate and the future of climate change negotiations worldwide.

HFCs are organic compounds commonly used as refrigerants, insulating foams, and aerosol products. The growth in HFCs is primarily due to an expansion of air conditioner manufacturing. As tropical developing countries grow, their growing middle classes are driving a growing demand for air conditioning. HFCs are hundreds to thousands of times more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide. Ironically, as people attempt to cool themselves, they are warming the world.

Currently, HFC’s account for only 2% of total greenhouse gases, but, if unabated, they could rise to 20% by 2050.

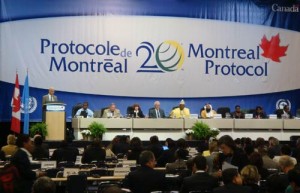

The increased use o f HFCs was a direct result of the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which sought to phase out the chemicals depleting the Earth’s ozone layer, particularly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). These CFCs were responsible for the hole in ozone layer over the South Pole.

f HFCs was a direct result of the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which sought to phase out the chemicals depleting the Earth’s ozone layer, particularly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). These CFCs were responsible for the hole in ozone layer over the South Pole.

The Montreal Protocol was a success in using international cooperation to reduce and eventually replace the chemicals causing the hole in the ozone layer. All United Nations members signed the agreement and consequently, the rate of CFC emissions is decreasing and the ozone layer is expected to fully recover.

Seeing success with the Montreal Protocol, China and the United States propose to use its framework to decrease their use of HFCs. The Montreal Protocol could mandate the replacement of HFCs with more climate-friendly chemicals like ammonia or dimethyl ether. Reducing and replacing HFCs has the potential to reduce 90 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2050 – this is equivalent to roughly two years’ worth of present global greenhouse gas emissions.

According to the American Security Project’s Global Security Defense Index, China sees climate change as a threat to its national security because it could harm both its internal security through its effects on water resources and regional security because it sees climate change as a ‘non-traditional’ threat that could cause conflict. By putting its support behind a push to reduce the global emissions of HFCs, China is therefore taking the necessary steps to improve its security by slowing down the rate of temperature increase.

As the two largest emitters of HFCs, China’s and the United States’ agreement sends a signal to countries like India and Brazil, which have not pledged to seek alternatives to HFCs yet. Through bilateral efforts, the United States and China will have more authority in persuading the remaining countries to join in their agreement.

Lastly, this new agreement could help build momentum to tackle larger climate issues, like reliance on fossil fuels. Seeing room for compromise and cooperation between China and the United States, the two countries may be able to lead the world in dramatically reducing our contribution to greenhouse gases.