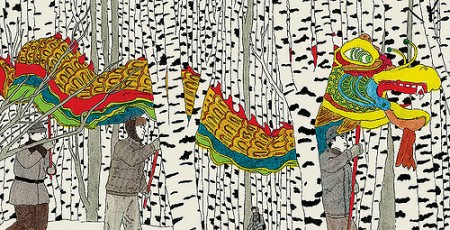

masha krasnova-shabaeva / flickr

masha krasnova-shabaeva / flickr

Beyond Appearances: China-Russia Drills in the South China Sea

China’s Defense Ministry announced last Thursday that China and Russia will carry out joint naval exercises in the South China Sea. The two countries are united in their dissatisfaction “with the current Western-derived notion of international order”. Considering Russia’s record of deepening ties with states that have tense relations with Washington, news of closer military cooperation comes as no surprise. However, theorizing about a rising Russia-China axis strong enough to reshape geopolitics is still premature though both countries will play into this role for its deterrent value.

Russia and China have conducted mil-mil exercises before, but these stand out because they are being held in the South China Sea. On China’s part, the drills are likely a response to the international tribunal’s rejection of China’s maritime claims, as well as THAAD deployment to South Korea. Russia is also an outspoken critique of US nuclear expansion at its borders and sees merit in emphasizing the point with the help of an influential world power. Besides, Russian engagement lends to its Asian-Pacific pivot after fallout with the West. In a time of economic and diplomatic uncertainty, it is crucial for Putin to maintain that Russia has powerful connections in the global community. The assertion that one of them could be Xi Jinping seems plausible as, like Russia, China does not shy away from tactical intimidation.

However, the Russia-China relationship is far from reciprocal and trusting. China has structured all agreements with Russia to retain the upper hand. In an effort to mitigate the negative impact of sanctions, Putin signed a series of deals with Beijing, including a:

- $400 billion contract to export 1,000 cubic meters of gas to China

- Rental of Russian land in Siberia to Chinese firms at a cost of 250 rubles (less than $5) per hectare per year

- Promise of Chinese investment of $20 billion into Russia’s infrastructure.

These figures demonstrate a willingness to sell gas and lease land at significantly reduced prices, while foreign direct investment will extend Chinese influence over Russia. Essentially, China took advantage of Russia’s failing economy. The impression of teaming up with Russia to counter American power is, again, done exclusively in China’s national interest. Following Beijing’s pragmatic pattern, if push comes to shove, China is unlikely to sacrifice its top trading partner, the US. In the long-run, strengthening ties with the Kremlin on the off chance that US-China relations do deteriorate creates a rainy-day backup plan.

There is another strong moderating variable in the China-Russia equation: Vietnam. Incentivized not just economically, but for security reasons, Southeast Asian states are making some alliance choices of their own. There is growing tension between China and Vietnam over claims in the South China Sea. Russia is Vietnam’s key trading partner, ironically supplying the arms that will help Vietnam withstand Chinese coercion. To protect this arrangement, Russia has been hesitant to openly side with China during the Philippines versus China international arbitration.

However, Russia might be pushed to take the risk; the US’s 2016 decision to lift its arms embargo on Vietnam as part of Obama’s Asia-Pacific Rebalance has no doubt left Russia with the suspicion that its interests in Asia are being challenged by the US as well. While the US needs to show leadership, accusations of micromanagement in conflict regions hinders resolution. These criticisms can be softened if the US puts more faith in world institutions and strives to collectively address the South China Sea dispute. A good start is ratifying the Law of the Sea Treaty.