China’s New Arctic Strategy Challenges the U.S. in the High North

On January 26, 2018, the government of China issued its first official White Paper on China’s Arctic Policy, calling for a new strategy on how the country will engage with Arctic nations, promote sustainable development in the region, and exploit the Arctic’s vast resources. For nearly a decade, China has focused attention on the Arctic, with several high-profile transits of their icebreaker the Xue Long (Snow Dragon), an increasingly strong economic and diplomatic presence, and even military exercises in Arctic waters.

The White Paper is clear about China’s reason for their interest in the Arctic, saying “Global warming in recent years has accelerated the melting of ice and snow in the Arctic region.” In the last decade, since a drastic drop-off in sea ice in the summer of 2007, the Arctic region has undergone a remarkable change in state, from an Arctic Ocean perpetually enclosed in ice to one open to transit and human exploitation. Ice cover of the Arctic sea has fallen to levels unseen in human history, while the region warms at twice the rate of the rest of the world. Climate change has opened the region, and countries have rushed to fill the gap. China – which calls itself a “near Arctic state” – has been one of the most aggressive nations in exploiting the newly opened region.

In the new White Paper, China links their new Arctic Policy to the Belt and Road Initiative of drawing China together with its trading partners.

As I’ve written before, China’s One Belt- One Road policy is an ambitious strategy that directly challenges the U.S. around the world. The Arctic Strategy calls for a “Polar Silk Road” that would link the region together and foster “sustainable economic and social development of the Arctic.” First mooted in June, 2017, the Arctic was included in the Belt and Road Initiative as a third “blue economic passage” (the first two are a passage through the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean to Europe and a passage through the Pacific to Oceania and the South Pacific) that is “envisioned leading up to Europe via the Arctic Ocean.” Overall, the Belt and Road Initiative focuses on Chinese economic assistance that would build infrastructure to help connect far-flung countries regions to China via upgraded infrastructure and economic development. Some have likened it to a Chinese version of America’s Marshall Plan. Though unsaid in documents, this strategy is clearly a way to build economic, security, and cultural ties between nations in the Eastern Hemisphere, with China at the center.

For that reason, the Belt and Road Initiative is an indirect challenge to American hegemony along both the Pacific Rim and throughout Eurasia. However, it is not clear that the United States under the Trump Administration has made any effort to counter China’s growing influence. Although the Trump Administration is beginning to confront China on what it calls unfair trade practices, aside from a few fitful remarks by President Trump about an “Indo-Pacific Strategy,” it has not provided an American alternative to Chinese influence. With the Trump Administration’s withdrawal from the Trans Pacific Partnership on the first day of the new Administration, there could not be a stronger message to potential partners.

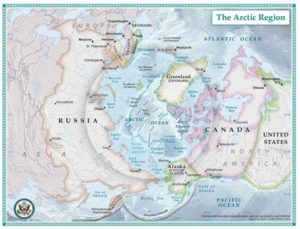

Political Map of the Arctic

Courtesy: US State Dept

This new Arctic strategy has been buttressed by direct, high level diplomacy with Arctic nations. In 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping held direct meetings with leaders of 7 of the 8 Arctic nations: Russia, Finland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Canada and the United States. In the eighth, Iceland, a senior Chinese delegation visited Reykjavik, touting the two country’s increasingly close relationship. Although there is no indication that U.S. President Trump discussed Arctic issues with President Xi, the Chinese leader did stopover in Anchorage, Alaska, where he met with Governor Walker, held a public briefing, and toured along the Seward Highway.

In these meetings, and in the new Arctic strategy, China claims there are four key areas of focus in the Arctic: shipping routes, oil and mineral resources, fisheries, and tourism. There are long-range reasons for China to be involved in each of these areas; China wants to streamline new sea lanes for exports, China wants to secure access to critical minerals for its economic growth (and to preempt competitors from seizing them), China needs to find alternatives sources of fish to supplement its increasingly empty seas, and Chinese people are demanding tourism to areas of clean air. However justifiable the reasons for Chinese interest are, they are also clear challenges to longstanding American interests.

Like other aspects of the Belt and Road Initiative, it is not clear that the Trump Administration has any plan to counter China’s growing influence.

In the Arctic, the United States has always been a reluctant power. Alone among Arctic nations, the United States has invested very little into its Arctic resources – with no real ports along Alaska’s Arctic waters, little military presence, and insufficient diplomatic engagement. While this changed slightly during President Obama’s time, with the first Presidential trip to the Arctic in September 2015, it appears that American interest to the Arctic has returned to its historic disregard. The State Department has not retained an Arctic Special Envoy, nor even replaced the recently-retired Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Oceans and Environmental and Scientific Affairs who had been responsible for Arctic relations. While there may be some funding for procurement of a new icebreaker in the upcoming 2018 budget, the US Coast Guard still limps along with only a 40 year-old heavy icebreaker and a medium icebreaker used by the National Science Foundation for scientific research. Though the Department of Defense recently updated their Arctic plan, they have not invested in the resources needed to meet the challenge.

President Trump’s sole public comments about the Arctic have been a garbled message in an interview saying (wrongly) that “The ice caps were going to melt, they were going to be gone by now. But now they’re setting records. They’re at a record level.” To the contrary, scientists uniformly agree that the volume and coverage of polar ice has been dramatically reduced over the past decade. In Trump’s meeting with Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg, there is no indication that the leaders of two Arctic nations discussed Arctic issues – though she had discussed the issue with Chinese President Xi.

In the past, I’ve written that the threat of conflict in the Arctic comes from a misreading of American interest and intentions. Now, with no coherent American message, presence, or messenger, that threat is higher than ever.

With the Trump Administration’s focus on confronting China, it may be a surprise that there has been little investment in confronting the Belt and Road Initiative. Seeing the priority that the Chinese government has placed on diplomatic overtures to Arctic states, and their demonstrated interest in resources within the Arctic, perhaps this is an opportunity to direct American attention to our forgotten Arctic shores. It is long past time.