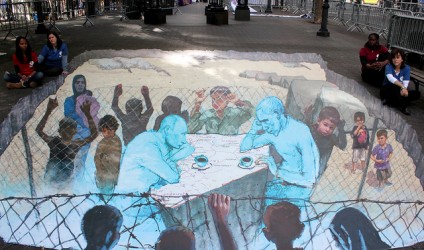

Oxfam International / flickr

Oxfam International / flickr

Collaboration with Russia in Syria: Setting Up the Endgame?

June drew to a close with two significant developments for Russia’s presence in the Middle East.

The first is the Presidents of Turkey and Russia calling for détente on June 29. The relationship of the two countries turned hostile in November when Turkey downed a Russian warplane which had flown into Turkish airspace. Last week, Erdogan apologized for the incident and Putin commiserated with Turkey following the Istanbul airport attack. Both countries announced intentions to make amends, which will entail Russia lifting the travel ban and trade restrictions on Turkey, as well as renewing collaboration on counterterrorism activities.

Following the Istanbul attack, Turkish officials claim that the IS suicide bombers likely came from Russia, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. Such reports actually come as an advantage to Putin because they justify continued Russian intervention in Syria.

Last September, after the international community first questioned Russian military buildup in Syria, Putin responded by explaining that Russia was acting “preventatively, to fight and destroy militants and terrorists on the territories that they already occupy, not wait for them to come to our house.” In addition, he called for the formation of a new international coalition against terrorism and extremism. However, the authenticity of this claim has been repeatedly questioned after evaluating Russian air strikes, which often lack precision, use disproportionate force and target US coalition-supported counter-IS forces. Moreover, Russia frequently denies operations, even though all evidence proves otherwise. The latest instance of this was a bombing at Jordan’s border. Another example was the hospital bombings in northern Syria before the start of the failed ceasefire.

There are geostrategic and economic reasons for Russian interest in retaining Assad in power. As well as a profitable trade in arms, Russian firms are invested in Syrian infrastructure, energy and tourism industries. Strategically, Russia’s placement of its Black Sea Fleet in Tartus gives Putin a foothold in the Middle East, allowing him to have more control over oil prices, for example.

However, from its inception, Russia’s war in Syria has had little to do with any of the above reasons. The intervention is a game of smoke and mirrors, used to send a message to the international community about Russia’s intended global role, and to detract attention away from domestic problems, including a worsening economic crisis, corruption and human rights violations.

On the surface, Putin’s war is necessary. Terrorist attacks like the one in Turkey with links to Russia make Putin’s case for action even stronger. This overshadows evidence that Russia’s IS problem was self-created and intentionally escalated, again, for domestic reasons.

The second significant event occurred on June 30, when the Obama administration proposed a new military partnership with Russia in Syria. The US and Russia would engage in mil-mil operations if Russia would agree to stop bombing US-backed rebel groups.

If Russian intervention is to be interpreted as political theater, in which anti-Americanism is the cornerstone of the United Russia party, Putin does not benefit from US cooperation unless it is portrayed as a Russian foreign policy victory (like the 2014 Syrian chemical weapons disarmament).

Washington’s outlook on the Syrian crisis has certainly evolved. As one senior administration official said, the war is “essentially a stalemate” which signals readiness for another defining compromise. This shift of priorities amongst some in the White House – from getting rid of Assad to ending violence – has potential to bring relief to the Middle East and Europe. But it also gives Putin another opportunity to boost his image–domestically and internationally – which could encourage sincere Russian efforts to bring an end to the crisis.

In addition, it seems that Putin might have his hands tied economically. On June 30, Putin addressed the eighth meeting of the Russian Federation’s ambassadors and permanent envoys at the Russian Foreign Ministry. He emphasized that Russia has no intention of being pushed into a “military frenzy” and being provoked “into a costly and futile arms race to divert resources and efforts from great socioeconomic development tasks at home.” Though this was said in the context of NATO buildup, this signals that Russia is running out of funds to continue military interventions abroad, including in Syria. Putin realizes that the Cold War arms race undid the Soviet Union, and that similar financial exhaustion could only lead to collapse.

These developments come at an opportune time for Putin. They allow him to save face.

However, a military partnership with Russia is only the first step if US goals are a long-term solution, not just a frozen conflict. In this case, the proposal would serve as a US gesture of goodwill preceding negotiations on Syrian transition and reparation. A rejected eight-point peace plan, submitted by Russia to the UN, has advocated for constitutional reform and nationwide elections overseen by key players in the Syrian crisis. The point of contention at the time was that Bashar al-Assad would likely remain a candidate in the presidential elections. Since then, it seems that the Kremlin’s support of Assad has wavered, while the White House has indicated that Assad would not have to step down immediately. This shift could encourage Russia and the US to meet in the middle.

It can be argued that it is dangerous to engage with Russia when its intentions are unclear. However, the fact remains that Russia has made itself a key player in Syria and has a place at the table. By moving to accept the broad terms outlined by the Kremlin, the US puts Putin in a position where he may have to back down from his own plan. If he does, Washington effectively calls Putin’s bluff.