Courtesy of Mariusz Kluzniak

Courtesy of Mariusz Kluzniak

Critical Issues Facing Russia and the Former Soviet Union: Governance and Corruption

When it comes to Russia and the other post-Soviet states, corruption is the subject of constant academic, policy, and popular debate. According to many, persistent corruption is the major factor undermining post-Soviet states from achieving broad-based political, economic, and social development along liberal-democratic lines. However, most analyses of corruption in Russia and the other post-Soviet states do not actually detail what their corruption is, the way that it endangers their development, or how they can fix it.

Corruption excludes many citizens of post-Soviet states from enjoying the benefits of economic development and the protection of their political and social liberties, alienating them from existing institutions and structures. Consequently, citizens of states with high levels of corruption are more likely to turn to potentially extremist groups whose struggles against the regime fuel further instability and often escalate into transnational conflicts. Finally, corruption makes it more difficult for American citizens and corporations to do business in post-Soviet states and engage in mutually beneficial economic and social partnerships.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev (Jürg Vollmer)

Assessing the type and amount of corruption present gives American policymakers and citizens the tools they need to engage constructively with their partners in post-Soviet states and forge effective solutions. This report analyzes trends in corruption among post-Soviet states, showing the differences and similarities between distinct states, regions, and periods of time.

In order to explore the political, economic, social dimensions of corruption, this report utilizes cutting-edge data from Transparency International and Global Financial Integrity (GFI)

This multi-level analysis exposes the distinct, yet interactive variables that shape the types and amounts of corruption that are present in states, especially among those that possess the shared legacy of Soviet Communism.

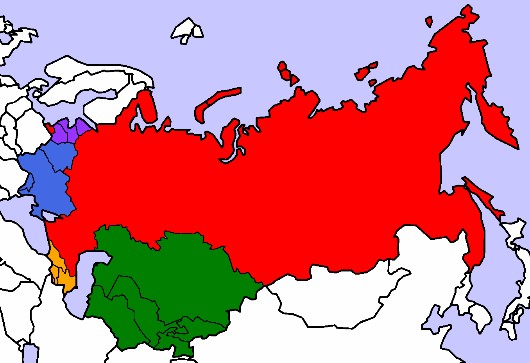

Baltics | Eastern Europe | Caucasus | Central Asia | Russia

Post-Soviet Regions and States

The following two topics – ‘Perception of Corruption’ and ‘Illicit Financial Flows’ – are at the core of the former Soviet Union’s challenge of establishing good governance and stamping out corruption. If you would like to see our overall findings, please consult the ‘Conclusions and Executive Summary.’

Perception of Corruption

One prominent measure of corruption is Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).

The CPI is the “most widely used indicator of corruption worldwide.” The CPI’s methodology “scores and ranks countries/territories based on how corrupt a country’s public sector is perceived to be” by using “a combination of surveys and assessments of corruption, collected by a variety of reputable institutions” with the scores ranging from 100 (very clean) to 0 (very corrupt).

Statue of Former Turkmen President Saparmurat Niyazov (Dan Lundberg)

The CPI focuses upon perceptions of public-sector corruption rather than “absolute levels of corruption in countries or territories” because of the lack of “hard empirical data.” Thus, while the score that the CPI renders is valuable, insofar as public-sector corruption is almost impossible to measure directly, it has some limitations that must be acknowledged.

Current Corruption Perception Index (CPI)

The following two charts show the current Current Corruption Perception Index (CPI) for post-Soviet states, grouping them regionally and individually.

Main Takeaways: According to the CPI 2014, the Baltics is the region of post-Soviet states that is perceived to be the least corrupt while Central Asia is perceived to be the most.

As this chart shows, the post-Soviet regions that have the highest perceived corruption, in descending order, are: the Baltics, the Caucasus, Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia.

Overall, there appears to be a general pattern of increasing perceived corruption from West to East, with the major deviation being that the Caucasus are perceived as less corrupt than Eastern Europe.

Main Takeaways: According to the CPI 2014, Estonia is the post-Soviet state that is perceived to be the least corrupt while Turkmenistan is perceived to be the most.

As this chart shows, the post-Soviet states with the lowest perceived corruption are: Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia; those with the highest are: Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan.

Importantly, when arranged from least corrupt to most corrupt, there is still a strong regional pattern present. Also, while international observers often point to Russia as the model of a corrupt, repressive state, a decent number of other post-Soviet states, particularly the Central-Asian states, are currently doing worse in terms of public-sector corruption.

Change in Corruption Perception Index (CPI) Over Time

The following two charts show the change in Corruption Perception Index (CPI) for post-Soviet states over time, grouping them regionally and individually.

Main Takeaways: According to the CPI, from 2012-2014, the Baltics was the post-Soviet region that experienced the greatest improvement in perceived corruption while Russia and Eastern Europe were the regions that experienced the least.

As this chart shows, from 2012-2014, the post-Soviet regions that experienced the greatest improvement in perceived corruption, in descending order, are: the Baltics, Central Asia, the Caucasus, Eastern Europe, and Russia.

While levels of perceived corruption remain high in Central Asia, there has been some improvement over the past few years and the Baltic states have reached new heights in perceived transparency and accountability. However, within Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Russia, there have been very small improvements and overall declines. These trends tend to correspond with Russia’s increasingly authoritarian posture and its increased intervention within surrounding states.

Main Takeaways: According to the CPI, from 2012-2014, Latvia was the post-Soviet state that experienced the greatest improvement in perceived corruption while Russia, Moldova, and Azerbaijan experienced the least.

As this chart shows, from 2012 – 2014, the post-Soviet states that experienced the greatest improvement in perceived corruption are: Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania; those with the lowest improvement are: Moldova, Azerbaijan, and Russia.

Illicit Financial Flows

Phantom firms and lax financial transparency requirements, especially in states that lack independent, participatory institutions, allow individuals and groups to appropriate a country’s wealth and potentially generate massive outflows of capital. The source of illicit financial flows (IFFs) often lies in trade-misinvoicing, or the process of individuals purposely committing fraud by mis-stating the quantity, quality, and value of goods.

Moscow International Business Center (Kirill Vinokurov)

The major types of trade-misinvoicing are: export under-invoicing, export over-invoicing, import under-invoicing, and import over-invoicing.

Export under-invoicing allows entities to transfer the difference between the market and stated value into offshore accounts, avoiding taxes in the process. Export under-invoicing allows entities to obtain extra export credits, and avoid both capital controls and state scrutiny. Import under-invoicing allows entities to avoid tariffs and VAT taxes. Finally, import over-invoicing allows entities to disguise the movement of capital out of a country, avoiding capital controls and possibly reducing the number of taxes they must pay to the government.

Downtown Minsk (Marco Fieber)

A significant portion of illicit financial flows (IFFs) find their way into the offshore bank accounts of the state’s elite, increasing its personal wealth while depriving the home market of capital for further development. As a result, high IFFs tend to correspond with increased inequality, economic stagnation, instability, and armed conflict. While periods of extraordinary economic prosperity, such as the unprecedented rise in petroleum prices during the 2000s, can stave off the inevitable backlash from the marginalized in states with weak institutions, they have rarely staved off the negative outcomes associated with high IFFs.

Nominal Average Annual Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs)

The following two charts show the annual illicit financial flows (IFFS) for post-Soviet states, grouping them regionally and individually.

Main Takeaways: According to GFI, from 2003 – 2012, Russia was the post-Soviet region that experienced the highest IFFs while Central Asia experienced the least.

As this chart shows, from 2003-2012, the regions that experienced the highest illicit financial flows (IFFs), in descending order, are: the Russia, Eastern Europe, the Baltics, the Caucasus, and Central Asia.

Interestingly, while Central Asia has the highest average level of public-sector corruption, as measured through the Corruptions Perceptions Index (CPI), it has the lowest level of illicit financial flows (IFFs), a measure of the explicitly economic nature of corruption. The Baltics and the Caucasus, although both have the lowest levels of public-sector corruption among post-Soviet regions, have moderate IFFs. Eastern Europe and Russia are similar in that both possess high level of public-sector corruption and high IFFs.

In line with this data, high levels of illicit financial flows (IFFs) seem to correspond to with more developed economies that possess authoritarian, inaccessible institutions. While the states of Central Asia possess the most restrictive, oppressive institutions, their lack of extensive economic relationships with outside entities, especially compared to other post-Soviet regions, means that their levels of IFFs remain limited. Likewise, while the states of the Baltics and the Caucasus possess the most accessible, representative, and transparent institutions, their higher level of economic interaction with outside entities means that they experience moderate IFFs.

Main Takeaways: According to GFI, from 2003 – 2012, Russia experienced the highest average illicit financial flows while Tajikistan experienced the least.

As this chart shows, from 2003 – 2012, the post-Soviet states that experienced the highest average illicit financial flows (IFFs) are: Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan; those with the lowest are: Moldova, Tajikistan, and Georgia.

As noted in the preceding analysis, there appears to be a correlation between states that have both more extensive interactions with the global economy and weaker institutions with higher illicit financial flows (IFFs). However, even considering this general pattern, the IFFs coming out of Russia seem disproportionately high and number the second highest in the world.

Adjusted Average Annual Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs)

While nominal illicit financial flows (IFFs) are useful for various types of analyses, adjusted illicit financial flows (IFFs) can further demonstrate the scale of economic corruption in a given region or state.

Whereas the preceding two charts presented illicit financial flows (IFFs) in nominal terms, on both a regional and individual level, the following two charts present them in adjusted terms. In particular, the average annual IFFs 2003 – 2012 are adjusted to their percentage of average annual GDP 2003 – 2012 so that one can compare the size of IFFs to that of the overall economy. As a result, from the adjusted figures, one can better judge how problematic IFFs might be in a given state or region, particularly in regard to their wider, economic repercussions.

Main Takeaways: According to GFI and Wolfram|Alpha, from 2003 – 2012, the Caucasus was the post-Soviet region in which average annual IFFs amounted to the highest percentage of average annual GDP and Central Asia was the region in which they amounted to the least.

As this chart shows, from 2003 – 2012, the post-Soviet regions that experienced the highest adjusted average annual illicit financial flows (IFFs), in descending order, are: the Caucasus, the Baltics, Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia.

Having adjusted the nominal average annual illicit financial flows (IFFs) to their percentage of average annual GDP, the trends that were partially evident in the initial analysis become much clearer. While Russia remains high, the Caucasus and the Baltics surge forward because of their high level of interaction with outside entities and the overall size of their economies, which are much smaller than that of Russia, being taken into account. In contrast, Central Asia with its low level of interaction with outside entities has low IFFs, especially when compared to the overall size of the regional economy.

Main Takeaways: According to GFI and Wolfram|Alpha, from 2003 – 2012, Belarus was the post-Soviet state in which average annual IFFs amounted to the highest percentage of average annual GDP and Ukraine was the state in which they amounted to least.

As this chart shows, from 2003 – 2012, the post-Soviet states that experienced the highest adjusted average annual illicit financial flows (IFFs) are: Belarus, Latvia, and Armenia; those that experienced the lowest are: Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan.

Similar to the regional level, at the individual level, having adjusted the nominal average annual illicit financial flows (IFFs) to their percentage of average annual GDP, the trends that were partially evident in the initial analysis become much clearer. Belarus, which experienced the second highest nominal average annual IFFs, moves up to number one in adjusted average annual IFFs, which total almost one-fifth of average annual GDP. Interesting, Eastern Europe has the largest discrepancy in adjusted IFFs because Belarus has the most while Ukraine has the least.

It is important to note that illicit financial flows (IFFs) do not represent the entire size of the shadow economy. Russia, which has high levels of nominal IFFs and moderate levels of adjusted flows, and other states may express different trends in economic corruption that validate or challenge the trends presented here.

Conclusions and Executive Summary

Overall Trends

Baltics

Since independence, the Baltic states have been the most effective of the post-Soviet regions in combating corruption. The Baltic states have relatively low levels of perceived corruption, their perceived corruption is improving over time, and their levels of illicit financial flows are low – moderate, especially considering its advanced level of economic development.

Many attribute the Baltics’ positive performance in creating accountable, transparent, and participatory institutions to their interaction with Western states and membership within Western institutions like NATO and the European Union. Other than exerting a positive influence upon the Baltic states, the interaction with the West may have shielded the Baltic states from Russia than more so than many of the other regions in this analysis, which may have allowed its improvements and prevented a backslide.

Baltic Way Commemoration, Riga (Pablo Andrés Rivero)

However, within recent months, as a part of its more confrontational stance toward Europe in general, Russia appears to be threatening the future sovereignty of the Baltic states. There are fears that Russia will attempt to do so based on its proposed stewardship of Russian-language speakers and the ability of those speakers to secede, along with the territories they occupy, to enjoy the protection of the Russian Federation. The threat is particularly pronounced for Estonia because of its comparatively larger population of Russian speakers. However, as long as the Baltic states enjoy the protection of Western institutions, there appears to be little potential for a backslide in anti-corruption measures.

Eastern Europe

In recent years, Eastern Europe has been rocketed by conflict, most evidently in the continued struggle for control over Ukraine’s eastern, separatist provinces.

Eastern Europe possesses levels of moderate – high levels of perceived corruption and its perceived corruption is worsening / stagnating over time, possibly because of the destabilization that has gripped the region and increased Russian intervention in the region’s domestic affairs. Economically, Eastern Europe’s levels of illicit financial flows (IFFs) are moderate – high, but mostly because Belarus has the second-highest levels among all post-Soviet states. Belarus’ close connection with Russia, which itself possesses the second-largest IFFs in the world, could be a major contributing factor.

House of Government, Minsk (Marco Fieber)

Prior to the Euromaidan revolution, Ukraine suffered from high levels of corruption under former, pro-Russian president Yanukovych. After the revolution, the government has released its grip on civil liberties in particular, but is still experiencing high levels of perceived corruption. The stagnation is possibly the result of doubts about President Poroshenko’s ability to root out the same incentives toward corruption that existed during the pre-revolutionary administration. It is also unclear what influence that Russian institutions and norms will exert upon the secessionist republics of eastern Ukraine like Donetsk. In line with the foregoing analysis, if Russian influence does increase, the outcomes for transparency and accountability will probably be negative.

Caucasus

Since independence, the Caucasus has been moderately successful in improving transparency and accountability.

Flame Towers, Baku (wilth)

Currently, the region has low-moderate levels of perceived corruption, its perceived corruption is improving over time, and its levels of illicit financial flows are low-moderate. However, like many of the post-Soviet regions, it has recently been the site of increased Russian interference, which could impede its attempts to consolidate and build accountable, transparent institutions.

Central Asia

Since independence, the states of Central Asia have probably experienced the worst political and social repression of the other post-Soviet regions. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan share the dubious distinction of the Worst of the Worst rating according to Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2015, two of only nine states in the world to possess it currently.

Central Asia possesses moderate – high levels of perceived corruption, but there are some bright spots. The region’s perceived corruption is decreasing over time and its levels of illicit financial flows (IFFs) have been fairly low.

Islam Karimov, Uzbek President (Alexandra (Sasha) Lerman)

However, as the region continues to grow economically, the lack of transparent, accountable institutions could lead to higher IFFs with state elites appropriating the spoils of development. The danger is particularly acute in Central Asia because many of the region’s states are drawing closer to Russia in both institutional and ideological terms, and possess huge amounts of natural gas and other resources. The resource-exportation industry is particularly vulnerable to theft through trade-misinvoicing and the use of anonymous shell corporations to launder and hide ill-gotten gains in jurisdictions like Cyprus.

Russia

During the past few years, Russia has largely stagnated or regressed according to many measures of corruption. For example, freedom of the press appears to have contracted significantly along with expanded support for state-run media like RT, which espouses the anti-Western, confrontationalist narrative of Putin and his allies.

Downtown Moscow (Cheshire Cat)

As the preceding analysis has shown, Russia continues to possess moderate – high levels of perceived corruption and its perceived corruption is increasing over time. Russia’s level of illicit financial flows (IFFs) are the highest among the post-Soviet states and the second-highest in the world. It is probable that Russia’s high dependence upon resource-exportation combined with weak institutions is yielding a high level of elite-capture of revenues, leading to the very high IFFs. Even though the price of oil has gone down, there is still a lot of money flowing into the pockets of the much-reviled Russian oligarchs.

What Is To Be Done?

Corruption, in its various forms, is having a negative impact upon post-Soviet states and the United States’ relationships with them. While the causes of the trends in corruption and their solutions are still up for debate, the trends themselves are quite clear. At the very least, this report helps to provide the foundation for a more informed, constructive dialogue.

Shipping Containers, Common Target of Trade-Misinvoicing (Tristan Taussac)

In order to achieve greater levels of accountability and transparency, post-Soviet governments should focus upon both rooting out corruption at its source rather than merely deal with its effects and empowering civil society to play an active role.

For example, Kazakhstan has recently initiated a ten-year plan that seeks to eradicate corruption through “creating conditions under which the use of official powers for personal gain will be unprofitable and impossible” and emphasizes that a “successful fight against corruption” requires “the ability of citizens to participate directly in solving local issues.” Post-soviet states should pursue policies such as these both on their own initiative and in coordination with larger international organizations like the OECD and agreements like United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC).

In regard to corruption in post-Soviet states, the United States can pursue a number of policies: supporting anti-money laundering measures; requiring all legal entities, such as shell corporations, to list their beneficial owners, rather than nominees who shield the beneficial owners from prosecution; pressuring tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions to give information to law-enforcement officials; and helping post-Soviet states to build capacity so that they can crack down on trade-misinvoicing and tax-avoidance.

Through implementing these measures, local governments and United States can work together in supporting post-Soviet states in their transition toward more accountable, transparent, participatory, and just societies.

Thank you

This is an excellent article. I have the following comments:

1. In authoritarian states, economic agents may not fell quite free to share their honest opinions regarding corruption for fear of retribution (even if survey results are strictly confidential). Moreover, the response or perception is subjective–they may reflect the experience of the respondent rather than the ground reality. For example, if a firm is favored by a political establishment, its senior officers may give a positive feedback on corruption while if a business is hurt by the status quo, its officers would return a negative perception.

2. IFFs also have their limitations but on balance economists prefer a quantitative estimate based on reported official data. Moreover, IFFs can be calculated over a much longer time span than the TI’s CPI or the World Bank’s Control of Corruption index (available starting 1995 or so).

3. One could run correlations between the CPI and the IFF rankings both on a level and ratio-to-GDP basis. I imagine the corerelation between the country rankings would be high (probably higher than 0.6). It is worth trying.

Best wishes,

Dev Kar

Chief Economist

Global Financial Integrity

Washington DC 20036