Dictating the Narrative: State-Controlled Media in Russia

Power is often associated with control of land, people, money – and nowadays – information. In Russia, the media is a valuable tool for the control of information to mediate public awareness and opinion. However, inconsistencies arise around state-sponsored media, independent reporting, and the Russian Government’s domestic perception as President Putin and the Kremlin work to control the dissemination of information.

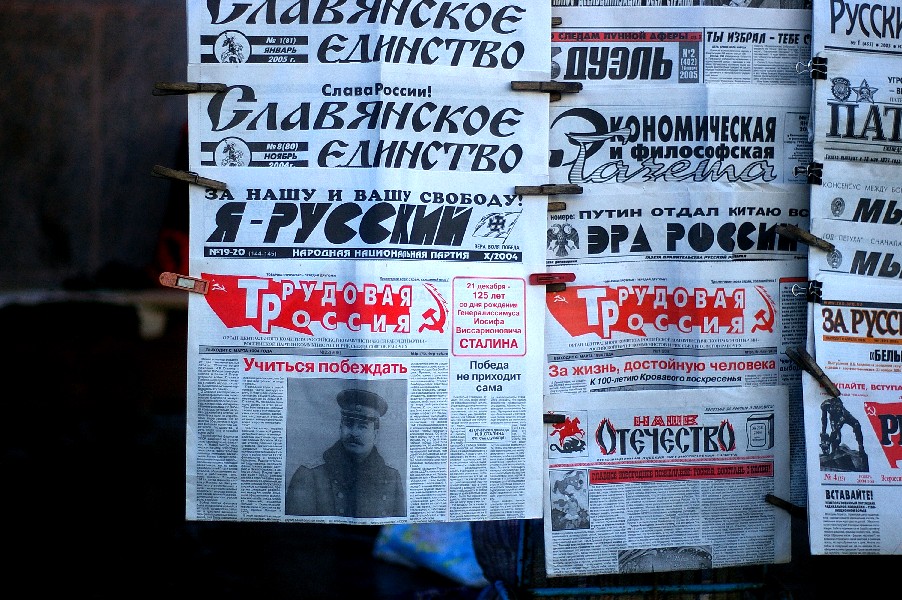

Television is the main media tool in Russia, with three out of four people watching state-sponsored television as their main source of news. Beyond major state-controlled networks, media outlets including newspaper, radio, and television networks are often run by state-controlled companies, such as energy-giant Gazprom, or companies with close ties to the Kremlin. Putin’s administration controls daily coverage, selects foreign and domestic content, and chooses what is “off-limits.” President Putin and the Kremlin have harnessed media as a powerful instrument to sway polls, rewrite news, and “achieve domestic and international goals.”

Controlling the access and distribution of information allows the Kremlin to dictate stories and facts to influence public opinion. Beyond overseeing which stories are released, the Kremlin will often “modify the narrative.” Releasing various, different stories with elements of truth increases the noise in the media environment. Thus, the audience faces not only an overwhelming amount of messages but also many different versions of the same story without knowing which one is correct.

Contradictions created by the “noise” in media with different versions of stories, controlled press outlets, and selective information, also create contradictions in public opinion. Recently, the Kremlin has become more worried about opposition media. Since the Ukraine crisis, the state has “intensified the pro-Kremlin and nationalistic tone of their broadcasts, pumping out a regular diet of adulation for Mr. Putin, nationalistic pathos, fierce rejection of Western influence and attacks on the Kremlin’s enemies.”

It seems that the pro-Putin media has been working; Putin’s approval ratings in May 2017 were 81%. Further, of the people who watch state-sponsored television for news, 84% approve of Putin, as opposed to 76% approval for those who do not.

In contrast, approval ratings for the government hover around 46%. Whether this reflects that 79% of Russians believe the government is corrupt in some way or that Putin himself is the hero who brought stability after 1990’s hardship and continues to be “part of a solution to [Russian] problems,” it is unclear.

The consequences of state-controlled media vary from cycles of self-censorship to building distrust towards independent news outlets and media in general. Threats like legal action or state-sponsored changes in ownership structure cause media outlets to have little incentive to continue publishing independent news. Journalist Maria Snegovaya, Vedomosti Business Daily Newspaper, describes the “waves of persecution” that roll out from the Kremlin to control media reporting. Increasingly severe restrictions for media organizations follow international and domestic developments and often correlate to damning incidents when media outlets become too bold or gain too much independence.

Independent outlets often do not survive government action if they do not compromise and publish stories from the Kremlin. Abba Redkina, Russia 24 News Channel, says that even independent online sites, such as Meduza, have incorporated “soft-news’’ from the Kremlin – “like discussing parks in Moscow” – alongside independent critiques of the Russian state.

As we look to newer technology, the internet poses a formidable threat as a democratic platform for public expression to states which control information channels. 71.3% of Russians, over 102 million people, have access to the internet today. In response, the growth of Kremlin-sponsored internet censorship has paralleled the rise of internet access in Russia. Social media platforms to organize anti-government protests, for example, prompted a 2012 law that “granted Russian authorities the power to block certain online content.” The law, focusing on websites related to “child pornography, illegal drugs, and suicide,” also contains a dangerously vague clause blocking “any type of illegal online material,” with open-ended language up for future interpretation.

Foreign media outlets should take note: Russian law now limits foreign ownership of traditional media outlets to 20%. This inherently makes news sources more Kremlin-dependent with greater likelihood for consequences for Russian-majority shareholders. International companies like Google, Twitter, and Facebook should also be careful of strict restrictions, including the out-of-country storage of personal data about Russian citizens, or risk being banned like LinkedIn was in 2016.

Information is a growing measure of power with recent cyberattacks, leaks, and controversy. President Putin and the Russian Government preserve domestic power by monopolizing the Russian information sector and through the deliberate distribution of mistruths. To protect United States credibility, there must be transparency and correlation between media communication and political action. Recognizing media manipulation, preventing biased framing of bipartisan issues, and maintaining an open mind are critical to strengthening international relations and securing domestic trust.