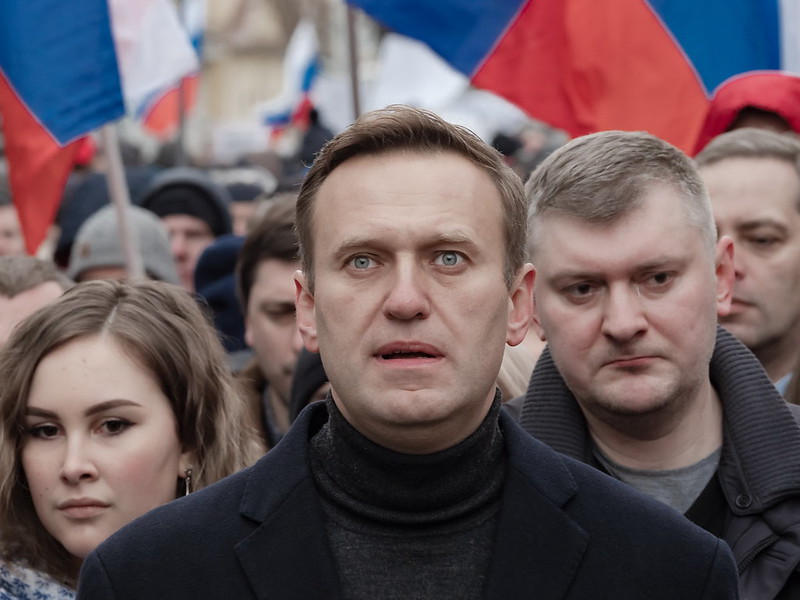

Image courtesy of Michał Siergiejevicz via Flickr

Image courtesy of Michał Siergiejevicz via Flickr

From the Kamera to Navalny: A Brief History of Russian Poisonings

This week, Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was discharged from the Charité hospital in Berlin. After spending 32 days there, Navalny’s coalition and Berlin doctors remain convinced that Navalny indeed became the latest victim of a long Russian history: the attempted assassinations of dissidents by poisoning. On September 8th, while Navalny remained in a coma at Charité, opposition volunteers linked to Navalny’s coalition were the targets of a chemical attack in Novosibirsk. While Navalny begins his physical therapy in Berlin this week, Western leaders are still considering an appropriate response to Russia’s use of chemical weapons against its domestic opposition. Should a serious deterrent not be deployed, history suggests we can expect more of the same from Russia going forward.

A Soviet Founding

The practice of using poisons has long served Russian and Soviet security forces as a discreet and effective means of silencing critics of the state. Over the past century, Russian and Soviet dissidents have succumbed to, or fallen seriously ill from, this Soviet-founded method of containment.

In 1921, the Soviet Union’s “poison factory” began research on weaponizing biological and chemical agents. Under Stalin, it was renamed “Kamera,” the Russian word for “Chamber.” Its history has included multiple closures and re-brandings, but no matter the official name under which it operates, its products have continued to be refined and developed as Federal Security Service (FSB) and Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) researchers have kept to the Cheka’s original ambition: “combining known poisons into original and untraceable forms.”

A Russian Tradition

In the century since, Soviet and Russian security forces have employed these biological and chemical agents in Russia and abroad. In 1978, Georgi Markov, a defected Bulgarian writer, fell ill and died after a man punctured his leg with an umbrella while waiting for a bus on the Waterloo Bridge in London. The tip of the umbrella carried a metallic pellet, which entered Markov’s leg and released ricin into his bloodstream. The assassination was suspected to be the work of a KGB agent.

In 2004, while running against Russian-favored Viktor Yanukovych in the Ukrainian presidential race, pro-European candidate Viktor Yushchenko fell mysteriously ill after dining with the head of Ukraine’s security service. It is suspected that the Kremlin worked with Ukraine’s security service to poison Yushchenko; Austrian doctors established that the substance ingested was dioxin. Arnold Schecter, an expert on dioxin at the University of Texas School of Public Health, told The Washington Post in 2004 that if someone attempted to deliberately poison Yushchenko, it was done by someone who “was very clever and very knowledgeable.”

In the same year, Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist critical of Putin’s escalation in Chechnya, lost consciousness on a flight to North Ossetia after drinking tea. When she awoke, a nurse at Rostov regional hospital whispered, “My dear, they tried to poison you.”

Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB and then FSB agent, confirmed that Putin’s Russia still operated the Soviet-era poisons lab meant to research and produce toxic weapons for the same past purposes. Litvinenko was killed in 2006 after ingesting tea laced with radioactive polonium-210; before his assassination, he had taken interest in the investigation of Anna Politkovskaya’s death.

From 2008 to 2018, a number of individuals seen to threaten Putin’s regime found themselves victims of suspected Russian poisonings: Karinna Moskalenko, a human rights lawyer; Alexander Perepilichny, a Russian businessman and whistleblower; Vladmir Kara-Murza, a twice-poisoned opposition leader; and Sergei Skripal, a convicted spy.

A Signal of Putin’s Weakness, or Strength

On first thought, the recent attacks on Russian opposition players suggests a certain insecurity of Putin and his regime. For Russia to act so egregiously – and by a method that is not-so-discreet given the history with which we have come to be familiar – it must weigh the risk of international response less than that of Navalny’s influence. Dmitri Belousov, a former employee of Russian state television, admits, “what [Navalny] has done is completely out of their control. The Kremlin fights against any force that it cannot control, any opinion that it does not control.” Perhaps Putin fears transnational winds of change: from America and Europe’s protests for racial equality to Thailand’s protests against a monarchical government; from Hong Kong’s protests against extradition to Belarus’s protests against Lukashenko.

This posture could also be one of strength. The recent attacks on Navalny, opposition volunteers, and dissident blogger Yegor Zhukov, could signal Putin’s expired need for political balance. Since the recent constitutional amendments fundamentally extended Putin’s presidency to 2036, the need for domestic balance may no longer exist. The complete removal of notable opposition – rather than keeping them around but at bay – may just be the Kremlin’s new policy in the era of a new constitution.

The Need for an Effective Response

The U.S. response to Navalny’s poisoning has been slow and relatively muted, a reaction which threatens the security of U.S. and allied actors abroad. Earlier this year, U.S. leadership failed to respond to reports of Russian bounties offered for U.S. troops in Afghanistan. The inability to deter Russia in each case has revealed a weakness in the international order: few options remain to pressure Russia to respect international norms. Sanctions and diplomatic expulsions have clearly failed.

An effective response will require the combined pressure of the U.S. and its allies. For instance, the use of banned chemical weapons could warrant a stronger response by Germany in which it could suspend the construction of Nord Stream 2, but German Chancellor Angela Merkel has already removed the natural gas pipeline from their already thin list of options. Until a U.S. president demonstrates a willingness to oppose such Russian behavior, and until other countries begin to wield more consequential leverage, we can expect Russian conduct to remain relatively unchanged. In the meantime, the security of U.S. and allied actors abroad will remain at risk, and those who challenge the Kremlin – from either Europe or Russia – have genuine reasons to fear for their life.