Photo courtesy of eu_echo on Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Photo courtesy of eu_echo on Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Lake Chad remains stable, yet Boko Haram still thrives. Part 1: The lake

Dar es Salaam, a refugee camp in Chad just across the border from Nigeria, was once under water. Situated on the outskirts of Baga Sola, a town near the southern pool of Lake Chad, the camp is home to 15,000 people fleeing war, poverty, and extremism. While the roots of the conflict are complex, climate change has profound effects on its drivers.

These drivers create a dynamic where terrorist groups such as Boko Haram thrive, exploiting the human suffering that lies at the intersection of unending conflict, deepening poverty, refugee flows, repressive government, and climate-change driven drought.

The reality of Lake Chad

Lake Chad is an ecological miracle: situated in the arid Sahel, it is a rare freshwater lake in an otherwise dry region. The lake is a critical resource for neighboring communities, who use its waters for fishing and agriculture.

Lake Chad is often a poster child for human- and climate-induced water loss. Between 1963 and 2013, the lake lost 60% of its water volume. Recurring droughts and overuse stressed the lake’s resources.

By the 1990s, severe droughts from the 1970s and 80s had shrunk the lake from 35,000 sq. km to 2,000 sq. km. It has since recovered to around 14,000 sq. km and has remained constant for the past few decades. While the water volume has remained stable due to groundwater recharge, the growth of plants has inhibited movement and fishing on the lake.

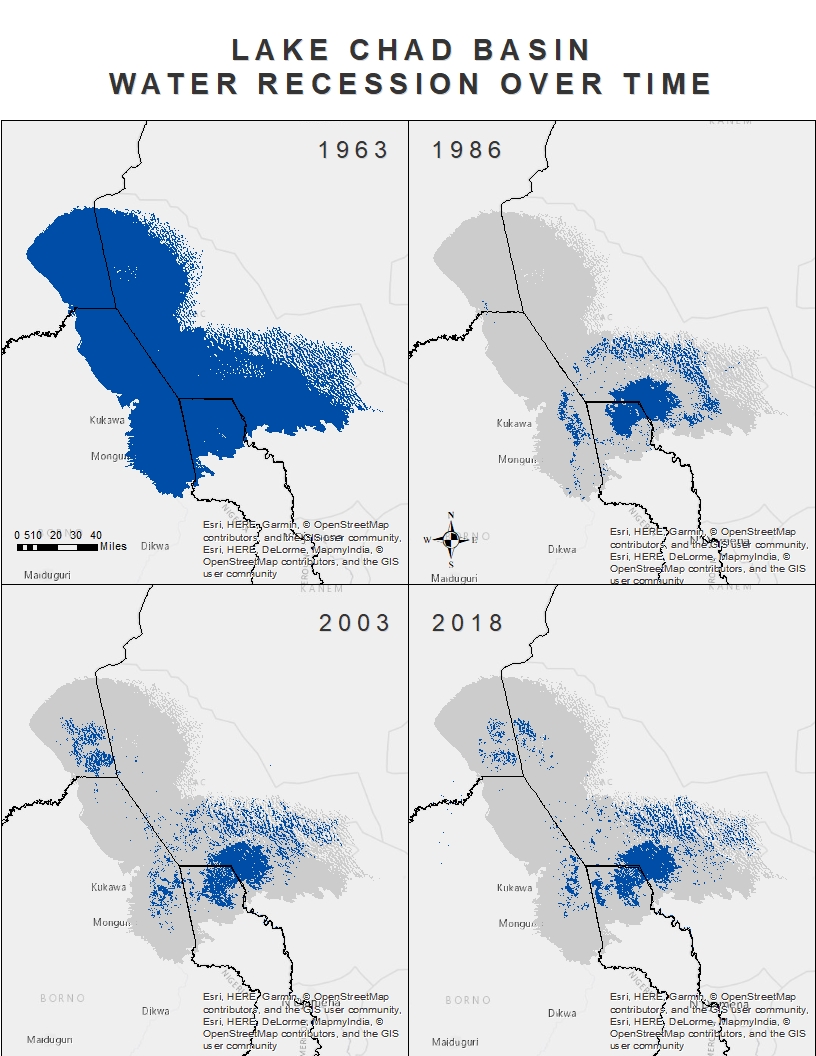

Lake Chad is far lower than its original extent, and high rainfall and temperature variability are undermining the livelihoods of surrounding communities. These conditions are most prominent in the northern pool, which continues to fluctuate. In the following figure, the upper left represents the full extent of the lake in 1963. Each of the subsequent maps show the lake extent during their respective years.

Map by Laura Sigelmann, 2019 (all rights reserved). Data from Landsat 1-8, available at earthshots.usgs.gov.

The impact of climate change

As of 2019, 10.7 million of the lake’s 17.4 million people required humanitarian assistance, while 2.4 million had fled their homes. Cycles of poverty and violence decimated the resilience of lake communities. Lake Chad has been called “the world’s most complex humanitarian disaster” due to the confluence of extremism, climate change, poverty, and violence. Many communities have been forced away from the lake into dry and inhospitable terrain.

Climate change will likely cause more extreme weather events and increasing temperatures in the Sahel. This plays out primarily in the northern pool, which fluctuates with changing rainfall. Higher temperatures also lead to an increase in vegetation, which slows water movement and hampers fishing and transport. The unpredictability will worsen poverty and food insecurity, further destroying livelihoods and breaking social bonds of communities already under stress.

This spells bad news for communities already under immeasurable pressure.

“The unpredictability of rains means that people are just giving up,” report author Janani Vivekananda said. “After the third or fourth failed harvest, not knowing when to switch from fishing to farming, the offer of a livelihood of food every day and business loans becomes more attractive.”

The importance of livelihoods and resilience

Lake Chad was once a cornerstone of cross-border trade supported by a vast network of income-producing activities. Fishing, agriculture, trading, and other livelihood systems gave locals coping mechanisms to adapt to natural and human-induced changes in the lake’s levels. Despite high rates of poverty, low development, and political marginalization, communities were more resilient in the face of climate change and drought due to their access to the lake’s wealth of resources.

The resilience of communities was chipped away during the 1970s-1990s. Severe droughts in the 70s and 80s caused people to follow the receding shoreline, increasing the population stress on resources. Structural adjustment programs, budget problems, and population growth diminished jobs and economic prospects in the region. Poor governance undermined traditional systems and marginalized communities on the lake.

By the time Boko Haram emerged in 2002, the regions surrounding Lake Chad were facing drought, poverty, food insecurity, corruption and inequality, and political marginalization. In 2009, the group started violently attacking villages in the Lake Chad basin, leading to further waves of migration. Forced evacuations and military responses restricted access to the lake.

Boats were outlawed due to their use by Boko Haram. Cattle, unable to graze in inhospitable terrain away from the lake, died. Crops went unharvested. The network of income-producing activities, many communities’ coping mechanisms, was no longer available.

For more on how Boko Haram exploits climate effects, see Part 2 of this post.