Turkmenistan President Berdimuhamedov presents Putin with an Alabai puppy named Verny. Attribution: kremlin.ru, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

Turkmenistan President Berdimuhamedov presents Putin with an Alabai puppy named Verny. Attribution: kremlin.ru, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

The Implications of Russia’s Decline in its “Near Abroad”

Thirty years of conflict concluded in Nagorno-Karabakh last month as Azerbaijan took over the semi-independent region. Armenia and Azerbaijan’s northern neighbor, Russia, historically kept the conflict in check. But as the war in Ukraine has bogged down the Russian army, the country has lacked the military and political capital to maintain the status quo in the region. The war in Ukraine has weakened Russia’s ability to stabilize ethnic and political tensions in its near abroad, mainly in the Caucuses and Central Asia, and its failure puts U.S. strategic interests in the region at risk.

Russia has played a significant role in the Caucasus and Central Asia historically and into the modern day. Before independence in 1991, all the countries in both regions were a part of the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire. But even after independence, Russian influence in the region loomed large. The Soviet Union shaped the borders of Central Asia, which had significant implications on the national identities and politics of the territories. Russia has also been a focal point of foreign policy for countries in its near abroad, as shown through Russia’s formation of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which includes the Caucasian and Central Asian nations of Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

However, Russia’s power in the region has waned with the invasion of Ukraine, continuing a trend that began several years ago. Notably, during the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, Russia did not intervene in favor of Armenia even though they had a mutual defense alliance. Relations have worsened after the current conflict, as shown this month when Armenia did not participate in regular CSTO military exercises.

Whether Russia’s weakening influence in the Caucasus and Central Asia is seen as a positive or a negative is less relevant than the direct consequences of this shift. Russia has tried to enforce the status quo, which is conducive to its strategic interests, but can be seen as morally dubious. The question is not whether Russia is a force for good, but rather whether Russian influence in the region is better than the counterfactual. Lifting Russian influence in the region could lead to additional instability and humanitarian issues. This is problematic for a U.S. beleaguered by more pertinent strategic interests, limited in its resources to respond military or diplomatically to further crises.

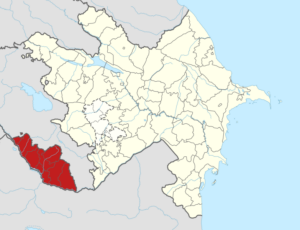

Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic in red. Created by NordNordWest. License: Creative Commons by-sa-3.0 de.

Risk of these crises may be determined by Russia’s inaction. In the Caucasus, the risk of future conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan remains, which could compound an already dire humanitarian crisis in Armenia. Following its success in the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute, Azerbaijan and its ally Turkey are focusing on securing transportation links that run through Armenia and link Azerbaijan to its exclave of Nakhchivan. This is occurring as 100,000 refugees have fled from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.

Recent political instability and border clashes in Central Asia show that Russian withdrawal could lead to violence. Kazakh unrest in January of 2022, when Kazakhs rioted over lifted price caps on liquefied petroleum gas, demonstrated dissatisfaction with the authoritarian regime. A Russian-led CSTO intervention put down the riots. In September of that year, border clashes between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, both allied with Russia and a part of CSTO, show the legacy of Soviet reign in the region and the tensions that remain.

Russia’s regional decline has significant implications for the U.S.’ strategic objectives. Central Asian nations have worked with the U.S. to combat terrorism. In addition, last month, U.S. President Joe Biden had the first presidential summit with all five Central Asian nations to strengthen counterterror operations and regional economic interconnectivity. Risks of violence in the region would put those missions at stake and further dilute America’s strategic capabilities. The U.S. also has a sizable Armenian diaspora which was angered by the government’s response to recent events.

For the U.S., future tensions in Russia’s near abroad will test of its ability to either prevent conflict or end it quickly. Humanitarian aid to Armenia to deal with the refugee crisis, which the U.S. has already announced, is a good start. However, further diplomacy will be needed to stabilize the region. The U.S. needs to work with the hand it has been given, to see the humanitarian and national security risks a Russian decline in its near abroad could have, and to act to minimize those risks.