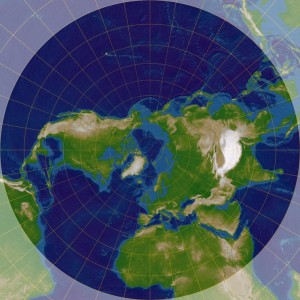

The Arctic at the Center of World Affairs

The Arctic is now at the center of world affairs. What was once a frozen ocean, closed to all but the most intrepid explorers, is now a venue for oil and mineral exploration, cargo transit, and even tourism.

The Arctic is now at the center of world affairs. What was once a frozen ocean, closed to all but the most intrepid explorers, is now a venue for oil and mineral exploration, cargo transit, and even tourism.

President Obama’s visit to Alaska for the GLACIER conference is an important reminder about America’s Arctic, and about the importance of climate change (the White House has a live blog of the trip at wh.gov/alaska).

America is an Arctic nation, and has been since the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 for $7.2 million dollars in gold, about two cents an acre. Then called “Seward’s Folly,” that decision would prove to be one of the most consequential for America, the people of Alaska, and the world. It provided access to Alaska’s vast reserves of oil, minerals, and fisheries. It provided the blessings of American citizenship to the people of Alaska (not trivial, given how poorly indigenous people were treated across the Bering Strait by Russian and Soviet administrations). And, it has given America a role in determining whether the 21st Century opening of the Arctic will happen peacefully and sustainably, or whether it will be characterized by conflict and a race to resources.

Central to our understanding of the Arctic is the question of “who’s Arctic is it?” It seems that some environmental organizations too often see the Arctic as a pristine environment for walrus and Polar Bears – not a place for people or industrial activity. On the other hand, industry has probably been too quick to assert that the resources of the Arctic should be immediately extracted. Cruise ships are planning trips through the Northwest Passage, even though the waters remain treacherous, shoals are uncharted, and search and rescue resources are sparse.

Now, as the world warms and the ice melts, the world is coming to the Arctic. At the geopolitical level, countries are racing to decide which part of the Arctic each owns, with the Russian government recently making news by claiming waters all the way to the North Pole. Likewise, Denmark has claimed waters beyond the Pole, conflicting with Russian claims.

Now, as the world warms and the ice melts, the world is coming to the Arctic. At the geopolitical level, countries are racing to decide which part of the Arctic each owns, with the Russian government recently making news by claiming waters all the way to the North Pole. Likewise, Denmark has claimed waters beyond the Pole, conflicting with Russian claims.

Virtually every country of the world is developing an Arctic strategy, and countries as far from the North Pole as Spain, India, or Singapore have become observers to the Arctic Council. China has asserted itself by sending icebreakers through the Northwest Passage (as an aside, when I was in Iceland recently, I was shocked by how many Chinese tourists were visiting Iceland). Some Chinese officials have even asserted that the Arctic should become an internationalized zone. None of this means that conflict is inevitable: in fact, the legal regimes of the Arctic are all well respected and followed by all Arctic nations.

Virtually every country of the world is developing an Arctic strategy, and countries as far from the North Pole as Spain, India, or Singapore have become observers to the Arctic Council. China has asserted itself by sending icebreakers through the Northwest Passage (as an aside, when I was in Iceland recently, I was shocked by how many Chinese tourists were visiting Iceland). Some Chinese officials have even asserted that the Arctic should become an internationalized zone. None of this means that conflict is inevitable: in fact, the legal regimes of the Arctic are all well respected and followed by all Arctic nations.

Today, most Americans forget that we’re an Arctic nation. Unlike the other countries of the Arctic Council – Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia – the Arctic has never been central to America’s cultural identity of itself. When I talk to Russians or Norwegians about, for instance, it is remarkable how closely their thoughts about their Arctic territories mirror American thoughts about the Wild West – this is a frontier where anyone can go to make their fortune or to get away from the troubles of civilization. This is to our detriment, and means that Americans and Alaskans are failing to meet the challenges of an open Arctic.

ASP’s work on the Arctic has focused on three overlapping themes: energy, climate change, and national security. We know that responsible exploitation of the Arctic’s resources can benefit the people of Alaska and of the United States. Moreover, we know that by developing policies to sustainably extract offshore oil reserves, we can effectively pressure our Arctic neighbors (like Russia) to also put in place policies that will guard against oil spills and environmental damage as they exploit their Arctic reserves. We know that climate change has affected the Arctic the most – but that damage from climate change also comes opportunities, as cruise ships and cargo vessels increasingly ply the waters of the Arctic.

Finally, American national security is threatened by an increasingly assertive Russian presence in their Arctic waters. Russia has re-opened as many as 15 military bases along their Arctic coast. Their re-opening of a base on Wrangel Island mean that Russian military base is far closer to Shell’s drilling rigs in the Chukchi Sea than the nearest American Coast Guard base on Kodiak Island, far south of the Bering Strait. We know that American policy can balance energy, climate change, and national security in the Arctic. But, we also know that America must focus on the region.

When I testified before Congress last year, I offered five examples of how Congress should address an opening Arctic, all of which would help America in the Arctic:

- Ratify the UN Law of the Sea Convention, so that the United States can fully participate in negotiations to determine borders in the Arctic;

- Increase funding for U.S. military presence by either the U.S. Navy or the U.S. Coast Guard in order to secure our sea lanes and provide for disaster response;

- Make a final decision on whether to approve and regulate offshore oil drilling;

- Elevate Admiral Papp’s role to a permanent Ambassador-level position;

- Raise the Arctic’s profile by regularly participating in Arctic-focused events.

Since my testimony, we should be pleased that the President and the Secretary of State have acted on recommendation 3 and 5, and have now proposed action on 2 when the President announced support for new icebreakers (they have long supported recommendation 1). However, Congress has the ultimate authority on each of these recommendations, and has largely failed to follow through. Hopefully, President Obama’s trip to Alaska, and the newly apparent cooperation between the Republican leaders of Alaska and the President shows a new willingness to engage on Arctic issues.

To answer the earlier question – who’s Arctic is it? – I think the answer must be: the Arctic belongs to future generations. It cannot simply remain a pristine environment devoid from human activity because, as the world approaches 9 billion people, we may need the oil and mineral resources for our economic well-being – and we almost certainly will need its vast fisheries in order to help feed the world’s growing population. Its territory cannot belong solely to the countries of the Arctic Council because what happens to the Arctic has impacts around the world: there is growing evidence that Arctic ice melt has actually helped caused extremely cold and snowy recent winters in eastern North American and Northern Europe. All of the world will benefit from long-term thinking on the Arctic, while we could all lose if we succumb to shortcuts and conflict. The Arctic belongs to future generations. We have a duty to remind ourselves of that when we make policy in the region.

Read More

ASP’s Andrew Holland’s Testimony before the House Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats: “The United States as an Arctic Nation: Opportunities in the High North”

ASP Reports

White Paper: “Americas Role in the Arctic: Opportunity and Security in the High North”

PERSPECTIVE: “The Arctic – Five Critical Security Challenges”

FACT SHEET: “Arctic Climate and Energy”

ASP OpEds

The Arctic: Last energy frontier?

America is Failing to Meet Challenges of a Changing Arctic

ASP Blog Posts

Methane: The Arctic’s Ticking Time Bomb

Norway’s Arctic Strategy: Profitability and Environmental Responsibility

Interior’s Review Says Shell was Unprepared for Arctic Drilling