La Fortaleza de PR Photo

La Fortaleza de PR Photo

The Economics of Debt in Puerto Rico

Recently, commentators have dubbed Puerto Rico as “America’s Greece.” While both Greece and Puerto Rico have major debts that cannot be repaid due to struggling domestic economies, the easy comparison leaves out important details about the debt crisis in Puerto Rico. With a more complete understanding of the situation in Puerto Rico, possible solutions become easier to identify.

Business Council for American Security Chairperson Dante Disparte – who was born and raised in Puerto Rico – was correct in his assertion in an interview with the BBC World Business Report that “much of the solution” to the crisis rests in Washington, DC. Indeed, Washington is in many ways responsible for creating the underlying economic issues that exacerbated the fiscal emergency.

Manufacturing

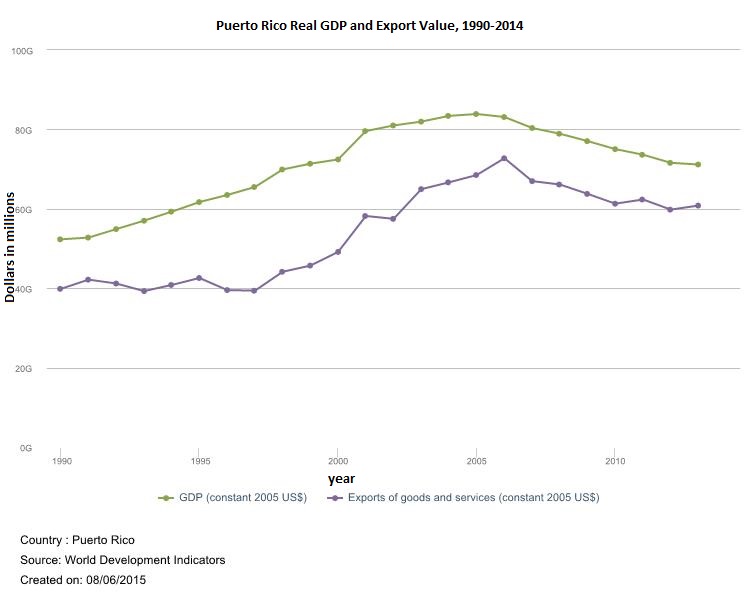

In 2006, Internal Revenue Service Code Section 936, which offered generous advantages to American companies operating in Puerto Rico, finally expired after a gradual phase-out. After the expiration of this tax subsidy, the Puerto Rican economy entered a recession from which it has not yet emerged. As the chart below shows, the decline in real (adjusted for inflation) Gross Domestic Product coincides with a decline in real export value. Export value peaked in 2006, and declined along with the total output of the Puerto Rican economy following the end of the business tax credit.

Manufacturing firms were major beneficiaries of the Section 936 tax credit. Its elimination and the loss of manufacture-for-export directly impacted the Puerto Rican economy and contributed to the severity of the ongoing debt crisis.

The decline in economic output makes it nearly impossible for the territorial government to keep up with ever-growing debt payments, and attempts at fiscal austerity only contribute to the economic decline. Even with an automatic increase in Social Security, Medicaid, and other transfer payments from Washington, local austerity is particularly undesirable in an economy featuring the high levels of government employment seen in Puerto Rico.

Energy

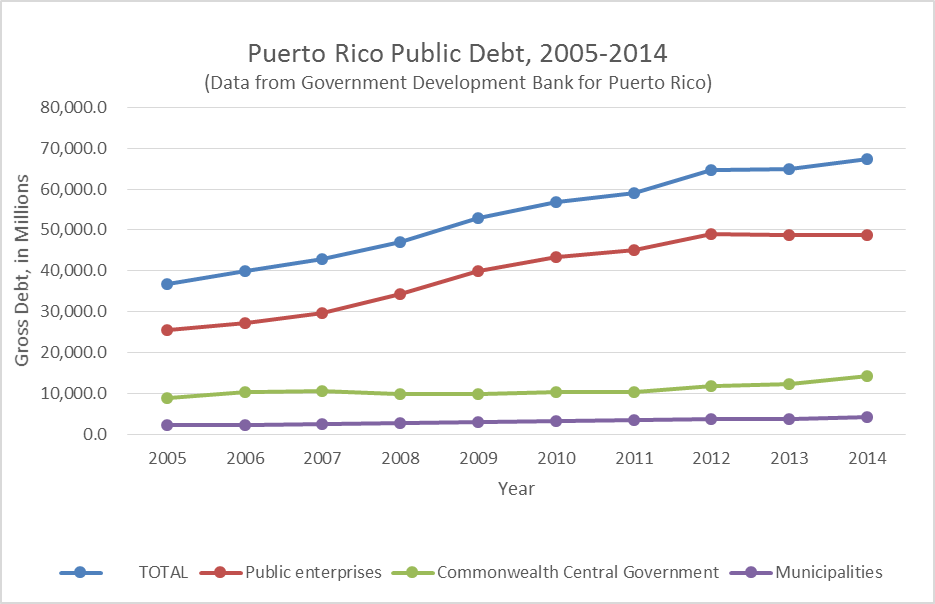

The single largest component of Puerto Rico’s total debt of approximately $72 billion belongs to the island’s inefficient utilities and other public enterprises, shown in red in the chart below.

As the central government and local municipalities have seen debt loads grow slowly from a low baseline, Puerto Rico’s public enterprises have piled up liabilities that comprise almost 70% of the territory’s debt.

PREPA (Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority) is responsible for the largest share of the public enterprise – and total – debt. The power utility owes more than $9 billion, and the agency’s poor management has left Puerto Rico unprepared for future growth in renewable energy while contributing to the current debt crisis. High energy costs have fueled the slowdown in manufacturing and export, which creates a potent combination with the expiration of the needed tax advantage. While still a large share of the island’s GDP, the manufacturing sector has declined by more than 30,000 jobs since the onset of recession in 2006.

Large entities like PREPA are the Puerto Rican institutions most in need of debt restructuring, but Puerto Rico’s public enterprises are not eligible for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection. A quirk in federal law restricts this access to the public enterprises of US states, another way Washington contributes to Puerto Rico’s inability to resolve its debt problems.

Unlike the situation in Greece, there are some clear ways to ease Puerto Rico’s economic difficulties. Access to Chapter 9 bankruptcy would allow public institutions like utilities and school districts to restructure their debt burdens into a more manageable payment plan. Along with eligibility for Chapter 9, Puerto Rico’s public enterprises like PREPA need better management, particularly to reduce burdensome energy costs and encourage development of renewable energy.

Reviving the tax break necessary to offset high costs of production could help the manufacturing sector lift the economy in general. Additionally, granting Puerto Rico an exemption to the federal minimum wage (which is almost equal to Puerto Rico’s median income) would allow businesses to hire less-skilled workers, and repealing the Jones Act of 1920 – which all goods shipped between Puerto Rico and the US mainland be carried on American ships – would allow for cheaper consumer goods and exports. Yes, Washington helped to create Puerto Rico’s problems. With good leadership, the federal government can also have a hand in solving them.