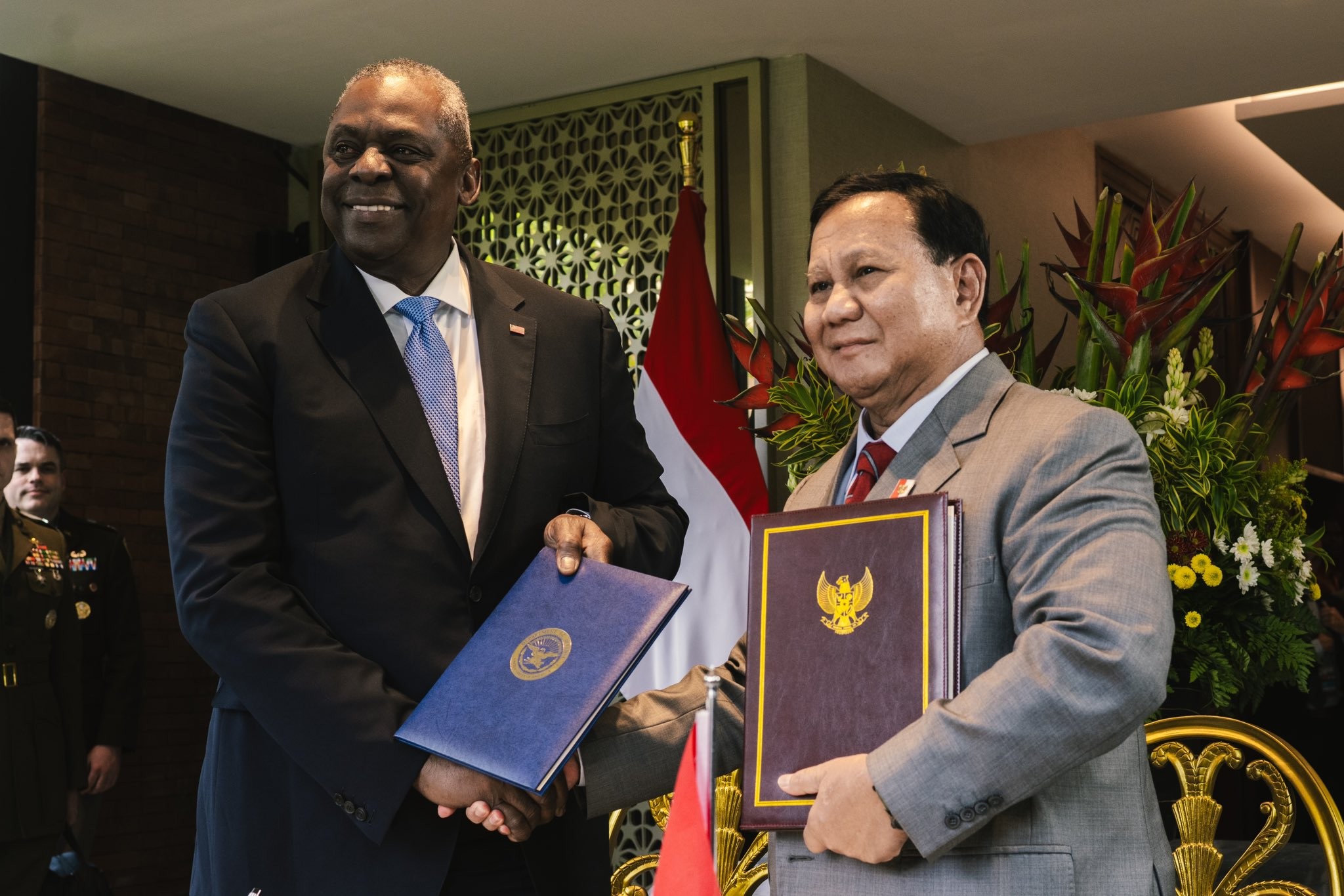

U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Indonesian Defense Minister and Presumed President-Elect Prabowo Subianto (2023) | Image Credit: Lloyd Austin on X

U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Indonesian Defense Minister and Presumed President-Elect Prabowo Subianto (2023) | Image Credit: Lloyd Austin on X

The Indonesian Presidential Election and its Implications for U.S.-China Competition

While the United States strengthens its alliances with traditional partners in the Indo-Pacific, other regional states oscillate between Washington and Beijing, seeking to extract maximum benefit from both sides. But as China imperils the sovereignty of its neighbors through expansionist behavior in the South China Sea, the United States is presented with an opportunity to draw these neutral countries into its orbit. The Republic of Indonesia is one of these countries, and having just held a major presidential election, there are implications for U.S.-China competition.

While often overlooked on the world stage, Indonesia is no minor player; it has the world’s fourth-largest population, a top-20 economy by gross domestic product, and a top-20 military by active manpower. Its position in Southeast Asia and proximity to the South China Sea are geopolitically important as Beijing seeks regional hegemony and Washington attempts to maintain a “free and open” Indo-Pacific. Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto is poised to become Indonesia’s next president, as official vote counts, which have been historically accurate, indicate his victory in the Indonesian presidential election last month.

Indonesia’s Foreign Policy History

Indonesia achieved independence from the Netherlands in 1949 and adopted an “independent and active” foreign policy, marked by securing its own national interests and partnering with other non-aligned countries rather than choosing sides between great powers. Despite this, at the beginning of the Cold War, the first Indonesian President, Sukarno, was closer with the Soviet Union. Following a government takeover by the anti-communist General Suharto, this dynamic flipped, and Indonesia sought closer ties with the U.S. While there have been periods of subtle bloc affiliation in its history, Jakarta has largely maintained its non-aligned foreign policy.

Caught Between Two Powers

As U.S.-China competition has shifted attention to the Indo-Pacific, Indonesia’s importance has grown. Under outgoing President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, Indonesia has sustained its reluctance to pick sides, preferring a closer economic relationship with Beijing and a more robust security alliance with Washington.

China is Indonesia’s largest trading partner and second-largest source of foreign direct investment. However, China also represents a major security threat: its internationally–unrecognized claims over Indonesian territorial waters and the encroachment of its naval and fishing vessels have challenged Indonesian sovereignty. Regardless, observers have made note of Jokowi’s subtle preference for China, most likely stemming from his prioritization of economic and infrastructure development, an area where Beijing has greater influence.

The United States is Indonesia’s foremost security partner but lacks China’s economic influence over the island nation, something it is trying to remedy. Washington and Jakarta recently elevated bilateral relations to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” encompassing not only security cooperation but economic development and climate change coordination as well.

Continuity or Change?

The presumed winner of the Indonesian presidential election, Prabowo Subianto, is widely regarded as Jokowi’s handpicked successor, accentuated by the fact that Jokowi’s son will serve as his vice president. Recently, Prabowo has expressed warm sentiments toward both countries; he praised the U.S. for its support during Indonesia’s struggle for independence and acknowledged China as a “great civilization” that has contributed significantly to the Indonesian economy. Both points may indicate Prabowo’s intent to continue Jokowi’s policies and uphold Indonesian non-alignment.

However, Prabowo is not Jokowi; he hails from a military background and holds a more nationalistic worldview. In the years leading up to last month’s Indonesian presidential election, Prabowo had been critical of Chinese threats to Indonesian sovereignty and claimed Chinese workers had stolen jobs from Indonesians. Therefore, it is possible that Prabowo will attempt to counter Chinese influence by reinforcing defense ties and boosting economic relations with the U.S. This strategic re-alignment would also benefit Washington by allowing it to project power north from Australia through Indonesia to the Philippines, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea. Furthermore, Indonesia is one of three countries that controls the Strait of Malacca, a maritime chokepoint through which 80% of Chinese oil imports travel. Closer relations, and cooperation on administering the strait, between Washington and Jakarta could play a role in deterring China from further hostile activity in the region and, importantly, an invasion of Taiwan. The prospect of a blockade of the strait has concerned Chinese leaders since Hu Jintao articulated the “Malacca Dilemma” in 2003. While the feasibility of a blockade is highly questionable, Chinese leaders must contend with the possibility of their war effort being decimated by such an action.

Both arguments have weight. Non-alignment is deeply ingrained in Indonesia’s foreign policy DNA. This “independent and active” foreign policy has allowed it to reap the benefits from all sides without being marred down by bloc allegiance. Indonesia can continue to maximize its economic gains from China while ensuring security cooperation with the U.S. remains intact. However, U.S.-China competition is highly dynamic, and further aggressive action by Beijing could be an impetus for Prabowo to place his country’s bets on Washington.