The Grim Prospects of Reform in Sudan

This editorial was originally published on The Huffington Post Blog, by Daniel Wagner, CEO of Country Risk Solutions (CRS) and author of the book “Managing Country Risk,” and John Bugnacki, an Adjunct Fellow with the American Security Project (ASP) and a research analyst with CRS.

The Prospects of Reform in Sudan

In spite of declarations to pursue reform following South Sudan’s secession from Sudan in 2011, the political landscape in Sudan has remained bleak, with the government of Omar al-Bashir continuing to repress the country’s marginalized populations. In response, there have been increasing levels of armed conflict and protest activity against the regime, and both international and domestic organizations are calling for Bashir to be brought to justice for his crimes against the Sudanese people.

As Sudan has some of the highest levels of ongoing political violence in Africa, and given that numerous other autocratic regimes in the region have been toppled, it remains to be seen how long Bashir’s government may be able to continue to ignore demands for reform. If history is any guide, there is little reason to believe that Bashir will change his tune, particularly given that last month he was reelected to another term as President, extending his 26-year rule.

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir (U.S. Navy/Jesse B. Awalt)

Background

One of the United States’ greatest successes in its recent policy toward conflicts in Africa was the Bush (II) Administration’s role in brokering the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that put a formal end to the Second Sudanese Civil War, which had dragged on from 1983 to 2005. The Second Sudanese Civil War was one of the most destructive wars in recent history, with most estimates placing the death toll at more than two million, and involving countless instances of human rights abuse, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

South Sudan Prepares for Independence (UN Photo/Paul Banks)

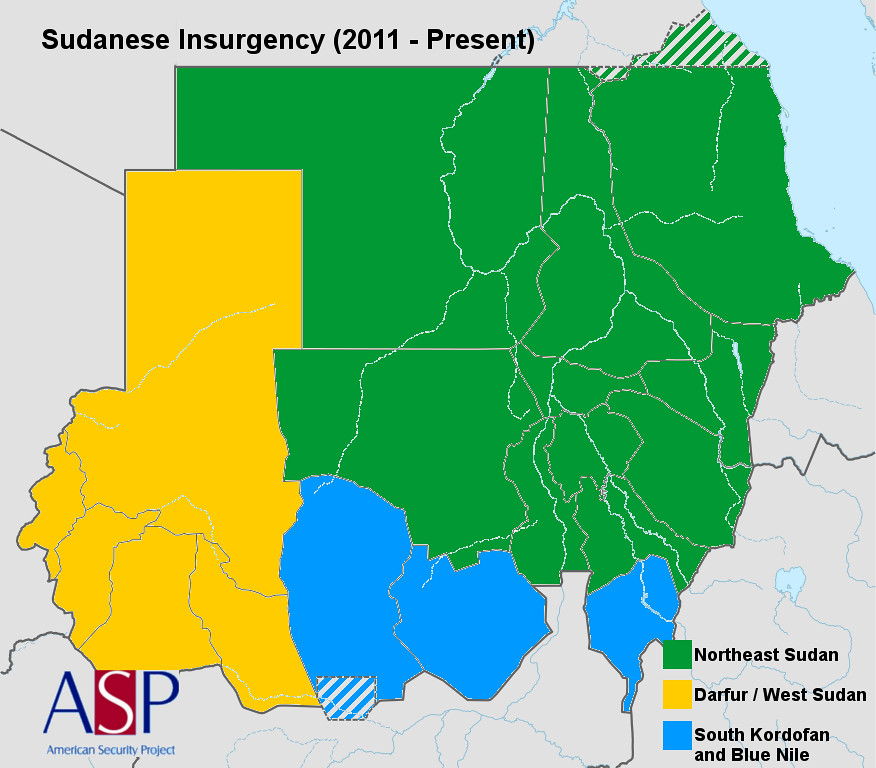

At the end of that War, the battle lines were drawn between the northeast of Sudan, which was poor but controlled the vast majority of government offices, and the country’s south and west, which had little governmental representation, but was resource-rich. Ethnic heterogeneity, the discovery of oil, and the legacies of colonial rule were all direct factors in sparking and sustaining the War, but those precursors did not disappear once it ended.

The South

In 2011, most of Sudan’s southern states decided through referendum whether they would remain part of the country or form an independent South Sudan. Blue Nile and South Kordofan — two other states that straddle the border between the North and the South — were supposed to hold similar referendums to define their federal relationship with Khartoum, but their governors, who belong to Bashir’s dominant National Congress Party, prevented the process from going forward.

Sudanese Insurgency (2011 – Present) (ASP/John Bugnacki)

As a result, when South Sudan split from Sudan, branches of the southern opposition groups that had fought for independence (such as the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM)) remained in these border-states and continued to fight against Bashir’s government. The most prominent of these groups is the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), which has fought intensely against government forces in the southern border regions. Yet, despite the continuing conflict with between the Sudanese government and southern militias, the overall geopolitical situation remains stagnant.

The West

The West of Sudan, also known as Darfur, was one of the regions hardest hit by the tail end of fighting during the Second Sudanese Civil War. The Darfur Peace Agreement of 2006 and the 2011 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur provided a framework for providing restitution to victims, conflict resolution, and political reform, but the Sudanese government has either not pursued the framework or has in some cases actively worked against its objectives.

Through these agreements, the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) — one of the major armed groups fighting the government in Darfur — agreed to lay down arms. However, as the Sudanese government failed to follow upon on promised provisions, some of the SLA’s leaders have returned to fighting alongside other groups who have never conciliated with the government, such as the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM).

The Adoption of the 2011 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (UNAMID/Olivier Chassot)

The United Nations African Union Peacekeeping Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) continues to provide humanitarian relief to the people of Darfur. However, Bashir’s government has recently called for the program to initiate its exit strategy as soon as possible. If the UNAMID were to leave, the fate of more one million refugees subsisting in camps in Sudan and Chad, and the civilians who suffer persistent attacks by the government-sponsored militias in Darfur (the Janjaweed), stand in the balance.

Even though groups such as JEM have expanded their reach from the West into parts of eastern Sudan, they have been generally unsuccessful in claiming territory from the regime. However, groups like JEM do appear to be reasonably successful in acquiring light and heavy armaments, having stolen them from the Sudanese army, and have amassed large stockpiles of weapons. JEM, SPLM-N and other groups have the arms and momentum to continue to fight Khartoum, but do not have much to show for it, either in terms of territorial gains or having forced the regime to meet their demands.

Coming in from the Cold

With the secession of South Sudan, much of Sudan’s oil wealth has disappeared, and the state has had to roll back its generous subsidy programs that it used to attempt to placate civilians for perceived widespread corruption and the lack of political freedoms. Similar to the behavior of most rentier states during boom times, Sudan made few investments in human capital and preferred to spend lavishly on unproductive or wasteful enterprises. As the country’s recent economic decline seems to be coinciding with increasing civil unrest against the government, Sudan is attempting to avoid revolution at home by pursuing increased engagement with the outside world, and very much wanting to leave the impression that it is breaking out of its radical, isolationist past.

In recent months, Sudan has succeeded in partially extricating itself from the pariah status that it has experienced in one form or another since the 1980s. Sudan is a member of member of the emerging Sunni Arab coalition in the Middle East, which consists of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and the Gulf States, and has participated in its ongoing military initiatives in Yemen and Libya. In doing so, it has distanced itself from Iran, a long-time ally. Sudan has also pursued partial reconciliation with the bordering states of Chad and South Sudan, against which it has had violent and protracted disputes, and is attempting to deepen its economic relationship with other African countries, such as South Africa.

South African President Jacob Zuma and Bashir (Gov. of South Africa)

Citing its cooperation with the U.S. and its allies in the Middle East on anti-terrorism programs, Sudanese officials are also pursuing closer ties with the United States while seeking the removal of its sanctions on Sudan. In response, the U.S. has recently relaxed some sanctions on Sudan, related to trade in communications equipment. Nonetheless, the U.S. remains disturbed by the Sudanese government’s domestic political situation, and unlikely to respond to Sudan’s overtures in a more meaningful way unless Khartoum stops its campaign against its own people and embarks on serious and sustainable political reforms.

The Future of Sudan and the Bashir Regime

As Bashir continues to refuse to reform, Sudan continues to experience a sharp increase in civil unrest. According to the ACLED (the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, a public database of political violence in African states), over the past few years there have been marked increases in both the reported incidences of protests, and government violence against civilians. Most of the major armed opposition groups, such as the SPLM-N and JEM, have become functionally united under the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF) banner. These armed groups and civil society organizations are calling for democratization, federalism, and the removal and prosecution of President Bashir for his alleged crimes.

In the wake of protests against the rollback of subsidies in 2013, a number of government officials expressed opposition to the regime’s violent crackdown. Bashir subsequently fired the officials who had dissented and surrounded himself with his closest political allies. While the government has repeatedly announced multiple national dialogue initiatives, they have resulted in little progress, and some political analysts suspect they are aimed primarily at imbuing the government with a false sense of legitimacy. The Sudanese government continues to deny testimony from international observers, such as Human Rights Watch and UNAMID, that it is continuing to oppress and terrorize its people.

Newly Displaced Civilians in North Darfur (UNAMID)

Bashir is also the only sitting head-of-state who has been indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC), which has charged him with genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in Darfur. The ICC recently halted its investigations into Darfur and Bashir to focus on other cases, leaving little prospect of prosecution, and giving Bashir even less incentive to change his tune domestically. Indeed, given that he won the presidential vote earlier this year with 95% of the vote (which has of course been contested by international observers as grossly fraudulent), Bashir may be expected to continue to rule Sudan with an iron fist and not embark on meaningful political reform. Only a change of leadership will open the door to that prospect.

* Featured Image – Sudan Flag (Nicolas Raymond)