The Qa'im-Bukamal corridor. Imagery courtesy Google / geodata from Phillip Smyth

The Qa'im-Bukamal corridor. Imagery courtesy Google / geodata from Phillip Smyth

The Iran Threat Network along the Qa’im-Bukamal Corridor: a Flashpoint for Power Projection

With U.S.-Iranian nuclear talks set to resume on November 29th, a series of escalating UAV attacks serve as a dark reminder of Iran’s “greatest asset”, the Iran Threat Network: largely active in the border cities of Al-Bukamal (alt: Abu Kamal), Syria and al-Qa’im, Iraq.

This fertile 20 mile tract along the Euphrates, once an ISIS stronghold, has become a cornerstone of Iranian regional strategy more than 4 decades in the making. As the Iran Threat Network moves to consolidate power along the border and project influence across the region, its growing scope and aggression pose an imminent security risk to U.S. interests.

Activating the Axis of Resistance

Iran’s “Axis of Resistance” allows the Republic to project regional power and avoid direct confrontation. It is Iran Threat Network groups, not Iran itself, that are most likely to launch direct attacks against the U.S. and its allies. Without them, the regional balance of power shifts against Tehran.

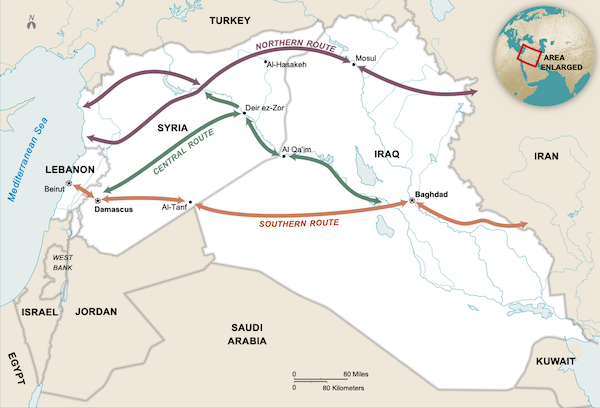

At the geostrategic core of Iran’s regional power play lies the Qa’im-Bukamal corridor, where a patchwork of proxies and clients secures a “land bridge” from Tehran to the Mediterranean. Commanding de facto control of the Qa’im-Bukamal crossing since 2019, Iran activated its first complete land route to the Mediterranean, passing personnel, weapons, and increasingly sophisticated drone technology to the doorstep of U.S. allies in Israel and Europe: what former Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Ed Royce once called “a strategic defeat.” US forces withdrew from al-Qa’im in 2020 following Iran Threat Network antagonism and Iraqi pressure.

Map by Lucidity Information Design for USIP

“A new era” of escalation

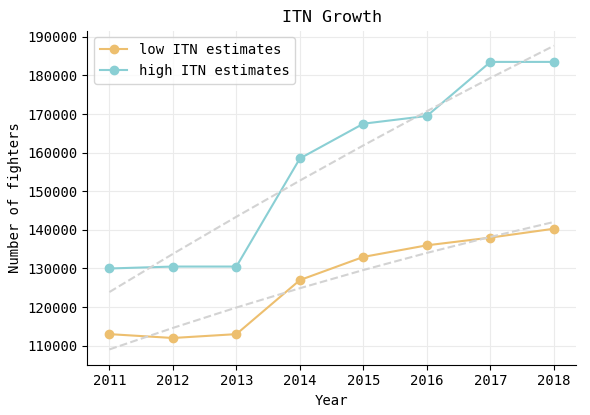

Competition for the vital Qa’im-Bukamal corridor persists as Iran Threat Network groups consolidate power and U.S. and Israel airstrikes target Iran’s growing “military empire”. With the assassination of Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps – Quds Force (IRGC-QF) paramilitary leader and Axis of Resistance “mastermind” Qassem Soleimani in late 2019, Iran Threat Network “managing partner” Lebanese Hezbollah hailed in a “new era” of operations against the U.S. Throughout the network, focus is pivoting to American forces, and recent attacks could mark a new phase of escalation absent ISIS opposition. A resilient Iran Threat Network fed by decades of conflict continues to expand and destabilize the region, with as many as 183,500 fighters across the region by 2018—up 71% from 2011. Iranian influence is the “new normal”.

Graph by Caroline Steel, based off of data from Seth G. Jones / CSIS

Deconstructing the Iran Threat Network

The Qa’im-Bukamal land bridge hub is one flashpoint in a greater transnational struggle. Iran has proxy management down to a science, but recent events indicate three main vulnerabilities:

1. Cohesion

Though ideological and structural variance of the Iran Threat Network may help Iran adapt its asymmetric capabilities to different environments, it also poses a challenge to IRGC-QF leadership already experiencing “shock waves” and disarray as a result of Soleimani’s death. Political infighting and internal division over Wilayat al-Faqih (ideological loyalty to Iran’s Supreme Leader) highlight the soft power tightrope Iran walks with many of its partners between local integration and supranational fealty.

2. Grassroots & nationalist pushback

Locals across al-Qa’im and al-Bukamal grow dissatisfied with rotating insurgent rule. Iran Threat Network partners may benefit from their relationship with Iran, but recent election results indicate public pushback as Iraqi officials capitalize on Shia political splits. In an economically-devastated Lebanon, a war-weary populace are frustrated with Iranian manipulation tactics.

3. Russian competition

Once close partners against ISIS and for Assad, rifts between Iran and Russia have begun to emerge across the Syrian theater after Russian forces sought control of the al-Bukamal Euphrates bridge. Though interests still broadly align, competition and ideological clashes could exacerbate strategic deviations.

U.S. foreign policy ahead of nuclear negotiations

As White House foreign policy shifts focus, President Biden must navigate loaded domestic and regional politics to manage Iranian influence. While nonproliferation will help mitigate catastrophic conflict, a new agreement could also allow ascendant Iranian proxies more operational freedom. Lacking new measures to address this issue separately from the nuclear crisis, a myopic “maximum pressure” policy will not subdue growing Iran Threat Network reach.

A small contingent of U.S. troops remains in Iraq and Syria: an important check against Resistance militias and alternative land bridges—but a physical presence leaves remaining forces tactically and legally vulnerable. An effective U.S. strategy will refocus on securing the crescent and countering the Iran Threat Network from two vantages:

1. From without:

supporting state development, unaligned Shia organizations, and political alternatives, and

2. From within:

capitalizing on disorder and economic hardship to magnify internal division, “weaponize” civil society, and loosen Iranian control.

The Iran Threat Network feeds off of weak states and weak institutions, and its battle-hardened members are more capable than ever. Iran is patient, and its memory long. As Iran continues to leverage the Axis of Resistance as a force multiplier and hone sophisticated asymmetric tactics, a comprehensive U.S. strategy must double down on disrupting the vicious cycle of encroaching Iranian hegemony in collaboration with Arabian, European, and Israeli partners.