Burned villages & fields taken from a UNHAS helicopter in Nigeria.

Burned villages & fields taken from a UNHAS helicopter in Nigeria.

The Sahel: A Neglected Crisis in Africa

As America focused elsewhere for the past decade, France maintained a dominant counterterror position in the Sahel, an African region vulnerable to insecurity. But with the French pulling out, Washington must assess the threat terrorist groups will pose to regional stability. This includes how climate change in the Sahel affects the security risk these groups pose to the governments in the region.

Map of the Sahel region, which includes Burkina Faso, Chad, Eritrea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, & Sudan. – Source: VOA

Analysis of the Greater Sahel and Jihadist Groups

Temperatures are rising faster in the Sahel, with the region expected to be 1.5-3.5°C hotter than the world average by 2050. Droughts occur every other year, as the duration of the rainy season can vary 30% from year-to-year. With temperatures rising and water scarce, the amount of arable land is shrinking.

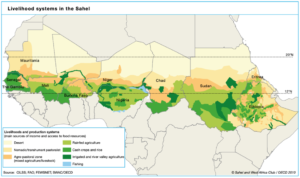

As shown below, 2/3 of Sahel’s residents depend on agriculture for their livelihoods. These communities need rainfall and stable temperatures. With 33 million people food insecure, the region is also afflicted with pervasive poverty and minimal development.

The Sahel region, divided by predominant sources of income and access to food. – Source: OECD, Philipp Heinrigs, 2010

In Nigeria, climate change has intensified resource competition between farmers and herders, causing intercommunal conflict. Yet the government has failed to effectively address it. In 2017, the Benue state passed an anti-grazing law to curb violence. This relocated thousands of herders to neighboring Nasarawa, where violence instead intensified. Within just 6 months, 260 people died.

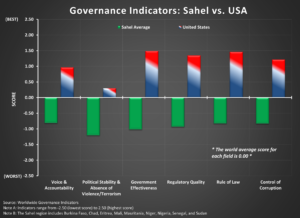

Measure of how the Sahel compares to the US and the world in indicators that measure good governance.

Extremism

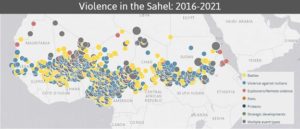

Governments’ inability to handle climate issues has allowed non-state actors to exploit shortcomings and pose a greater security risk. Some neglected constituents form militias, while others side with extremists, heightening the chances of violence in the Sahel.

Each point is attributed to an event, per the legend in the bottom right. – Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)

Terrorist groups like the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) sometimes present themselves as the alternative to the government. Government negligence reduces representation and expected services. Insecure people can be more inclined to either leave home, rebel, or find new sources of food and income in terrorist organizations.

Cross-border migration is common in the Sahel. Because of climate change, by 2050 an estimated 50 million additional people will be forced to migrate. Mass migration and desertification make it easier for terrorists to operate and harder for governments to defend.

Lake Chad

The Lake Chad area is an example of these ongoing issues. For centuries, Lake Chad supported millions in the region’s harsh environment. Yet in just six decades, the lake lost 90% of its volume. Now, with over 10.2 million in need, dwindling rainfall, rising temperatures, and desertification plague locals with droughts, unemployment, and banditry.

Residents of a community in Lake Chad, January 2017. – Source: Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Unfortunately, the Nigerian government fails to address the communities’ climate-induced problems. Ungoverned spaces prevent administrative action, while the military’s treatment of locals sows distrust. Meanwhile, by digging wells, facilitating commercial activity, and monitoring crime (albeit cruelly). ISWAP’s jihadist proto-state in the Lake Chad region preys on people’s climate-driven grievances. This makes it significantly harder for Abuja to defeat the group.

As the climate changes, more people will experience food insecurity and fight over resources. Such conflict and insecurity empower jihadists. So as local climate change issues continue to go unaddressed, the cycle of instability repeats.

Implications for US National Security Strategy

Washington should work to suppress the potency of jihadist groups, especially those connected to international movements. Significant gains by these branches could inspire “lone wolf” attacks or enable regional groups to launch a transatlantic strike.

America also has a commercial interest in the Sahel, from export markets to rare-earth minerals. Nigeria is expected to become the world’s 3rd most populous country, which has implications for American competitiveness, especially with others vying for influence. An unstable region can prove difficult to trade with and affects global markets.

Regarding climate security risk, Sahel communities & governments lack three things:

- Modern technology and practices, specifically in climate-resistant agriculture and resource management (ex: irrigation techniques to improve water management).

- Administrative presence and capacity focused on good environmental governance to address constituents’ concerns and mediate disputes.

- Effective security responses to jihadists that rely on sound intelligence, good coordination among security forces, and sustainable tactics that avoid alienating locals.

In 2020, America provided $1.86 billion in humanitarian and economic aid to the Sahel countries. Additionally, the American military trains security forces on counter-extremist efforts through programs like the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership. Little has been done, however, to address the growing climate security risk in the region. Meanwhile, with previous attempts to disengage from the region, Washington has left international responses disorganized and underwhelming.

To address the issue, Washington should:

- Direct the US Envoy for the Sahel to host low-level dialogues with major parties, including France, to develop a coordinated response to the Sahel’s security risks posed by jihadists as a result of climate change.

- Participate in the Coalition for the Sahel to support their endeavors in the 1st and 4th pillars, specifically emphasizing concerns over climate change and good administration.

- Provide funds to NGOs and American educational programs that support locals with modern technology and practices specifically aimed to build climate resiliency.

Featured Image Photo Credit: Roberto Saltori