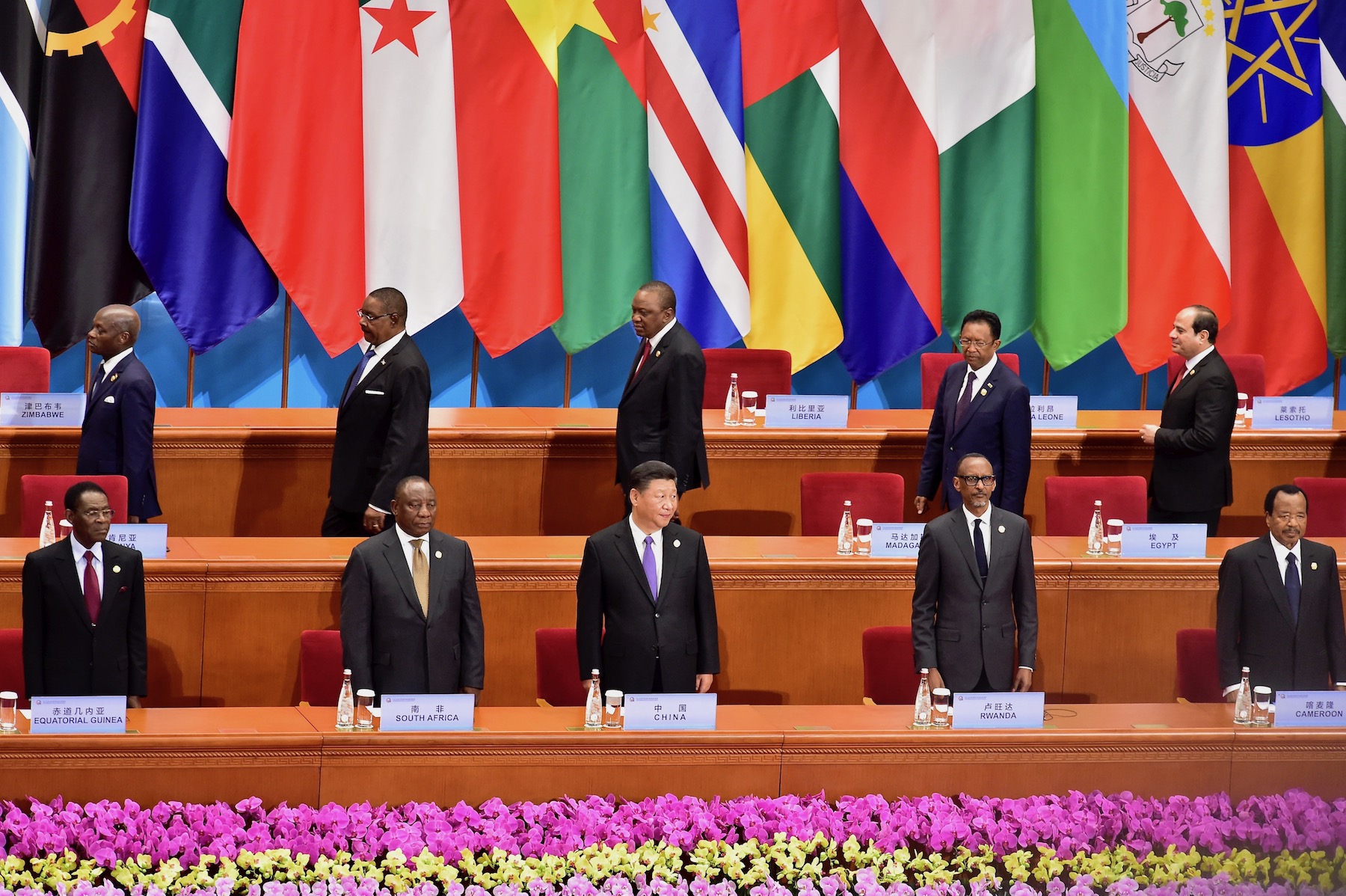

President Cyril Ramaphosa and President Xi Jinping co-chairing Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. (Photo: GCIS Govt. of South Africa)

President Cyril Ramaphosa and President Xi Jinping co-chairing Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. (Photo: GCIS Govt. of South Africa)

The U.S. is Losing the Great Power Competition in Africa

The U.S. has recently been stepping back from its involvement in Africa after protests and officials in several African countries asked the U.S. to leave. In Niger, protesters called for the removal of American troops from the country as the government revoked its military cooperation deal, resulting in the likely loss of a six-year-old air base. In Chad, a letter from the Chief of Air Staff implicitly threatened to end its security agreement with the U.S., leading to the withdrawal of Special Operation Forces and 75 other personnel. These two withdrawals mark a broader shift in the region away from Western nations and towards Russia and China. The loss of these countries as partners, as well as the U.S. military bases located there are serious blows to counter-terrorism operations in the region.

These withdrawals are also a significant concern for key mineral imports, as investment and engagement in Africa helped to strengthen America’s mineral supply chain. Currently, the U.S. is almost 100 percent reliant on “entities of concern”— mainly China. The increasing importance of minerals such as cobalt, graphite, and manganese, has led to global competition over African resources. Meanwhile, Russia and China both have used predatory mining practices to extract these key minerals.

Despite their destructive interference, China and Russia have risen above the U.S. in popularity in the region, a significant injury to American soft power in the region. Outlook on Russia and China has increased because of their willingness to trade in arms and in material support at levels at which the U.S. has thus far been unwilling to engage. In March, the head of U.S. Africa Command warned Congress of Russia’s expanding influence in Africa, primarily through disinformation campaigns and its Wagner mercenary group in such countries as Mali and Burkina Faso. China has also been expanding its influence through the Belt and Road Initiative, a development plan to bring more countries under Chinese influence.

A further cause for concern in Africa is the ongoing war in Sudan. As the civil war enters its second year, there has been massive displacement and need for aid. While the U.S. has been distracted by conflict in Ukraine and Gaza, and potential conflict in Taiwan, Russia has been playing both sides of the conflict for influence after the war. Previously, Russia had been a known supporter of the paramilitary group, Rapid Support Forces (RSF), but a recent trip by Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov showed Kremlin support for the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). While both sides have been accused of war crimes, the RSF has also been accused of crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing.

U.S. lawmakers and human rights advocates have been increasing pressure on the Biden administration to take a stronger approach to his policy in Sudan. Some lawmakers have even sent a letter condemning U.S. ally the United Arab Emirates (UAE) for its support of the RSF in violation of UN arms embargos. This creates a greater diplomatic challenge as the U.S. engages with the UAE in developing a ceasefire agreement in Gaza. While the U.S. has provided significant aid, an additional $100 million last month, its diplomatic response in addressing the conflict has thus far been insufficient.

The U.S. needs to reevaluate its diplomatic policy in the region to address why Russia and China have been gaining influence while the U.S. loses influence. African countries have grown tired of the U.S. and other western countries telling them how to govern and are attracted by Russia and China’s seemingly freer support. Despite U.S. attempts to expose the significant human rights abuses by Russian operators in the countries they’re supposed to be helping, many countries continue to engage more with Russia—and that shouldn’t be a surprise. For countries whose governments don’t respect human rights in the first place, it is easier to seek support from countries like Russia or China that also do not care about such things and that will assist in their goal to retain power at any cost. Another consideration is that U.S. law prohibits providing funding to coup governments, which significantly ties its diplomatic hands in trying to maintain access to countries for their resources and intelligence aid. At this point, there is a balancing act between the desire to protect in the short term against terror threats, and the desire to uphold principles of human rights and democratic governance—the very ideals that set the U.S. apart from Russia and China in the first place.

America’s loss of influence in the region is a great blow to its counter-terrorism strategy and key mineral access. Renewing African trust and engagement will be a difficult diplomatic challenge requiring both creative traditional and public diplomacy, but it is clear that U.S. policy cannot continue in the same manner.