U.S. Competitiveness: A Matter of National Security

by Dante A. Disparte, President, Harvard Business School Alumni Club, Washington D.C.

An Unlikely Prism

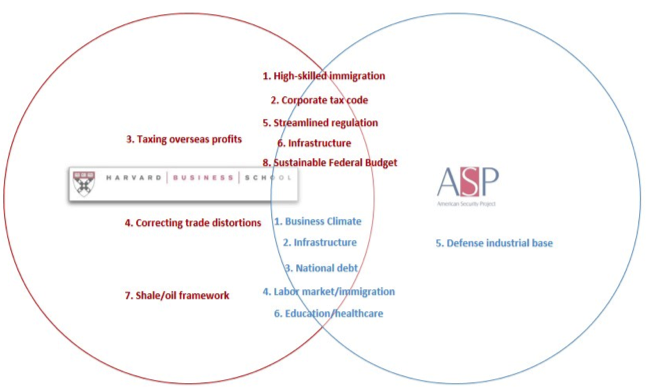

Rarely will you find agreement among military brass, business leaders and academics on issues of national security. Yet this convergence occurred between Harvard Business School’s (HBS) U.S. Competitiveness Project and The American Security Project (ASP), a bipartisan think-tank that emphasizes a holistic definition of national security to include military and economic strength. Both organizations independently surveyed the state of U.S. competitiveness and came to surprisingly similar conclusions.

HBS, for the first time in its history, is tackling policy issues of national scope. With the full weight of Dean Nitin Nohria’s office, competitiveness has fast become a top-of-mind concern among HBS faculty members and the message is being disseminated to the alumni network. This bold undertaking, under the leadership of Professor Michael E. Porter, (credited with codifying the notion of competitive strategy), and Professor Jan W. Rivkin, harnessed the views of more than 10,000 HBS alumni around the world, as well as members of the public. The findings offer a clarion call that urgent action is needed to arrest America’s declining competitiveness. The 2011 and 2012 surveys were not HBS’ only forays into the issues surrounding U.S. competitiveness. In fact, an entire edition of Harvard Business Review (HBR) published in March 2012 titled “Reinventing America” was devoted to this topic. The growing body of scholarship covering everything from the tax code and infrastructure to K-12 education suggests that this topic is here to stay and HBS intends on being a leading voice. More than 20 HBS faculty members have devoted their research and energy to issues of national competitiveness.

ASP, meanwhile, identifies deteriorating competitiveness as a clear and present danger to America’s national security. The commonalities of these two projects and the clarity from their distinct lenses offer a stark call to action (See Figure 1).[1] This call was echoed in the halls of power of the House of Representatives on July 10, 2013 as part of a joint effort between HBS and ASP to raise awareness and political will to tackle these issues head on.

A Positive Sum Game

Traditionally the word competitiveness, especially as it relates to strategy in a Porterian world, conjures up an image of winners and losers in an incessant struggle with competitive forces. In this state, economic actors (individuals, firms and, indeed, nations) compete for a finite set of resources. It is not without a sense of irony, thus, that HBS’ U.S. Competitiveness Project and faculty have revisited the definition of competitiveness. Against this standard, a nation is said to be competitive insofar as two conditions exist and function in lockstep. HBS faculty members define competitiveness as the extent to which American firms can compete in a global marketplace while maintaining and improving the standard of living of the average American.[2]

|

Figure 1: Competitiveness as a matter of national security

|

It is precisely this last point that makes HBS’ definition of competitiveness so profound. Indeed, both studies show that the average American has been forsaken over the last decade and many aspects of the American dream are increasingly out of reach. While the Great Deleveraging of 2007-2009 offered a spectacularly punishing economic correction, HBS research shows that the American job engine began to falter in early 2000.[3] This points to structural problems rather than a housing bubble bursting and the ensuing contagion, as the underlying cause of deteriorating competitiveness. In short, the middle class is finding it harder than at any time since the Great Depression to maintain their standard of living – squeezed between persistent unemployment (and under-employment) and rising costs. Exacerbating this trend, thousands of STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) jobs remain unfilled, now and in the foreseeable future, with the domestic labor force. Short of creating Keynesian work through deficit spending, the Federal government has shown little will and ability to tackle these underlying causes effectively.

Flying flags of convenience, American firms will continue to fare well in the global marketplace, as will graduates from elite institutions who are leading many of these firms. Global competition and its corollary, average American living standards, offers a refreshing alternative to the myopic focus on shareholder returns and self-enrichment that has become a breeding ground for moral hazard. Many firms that were too-big-to-fail (TBTF) or systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) did well in the recent financial crisis in privatizing profits while socializing losses.[4] At the same time, political gridlock and regulatory catch up continue to cost the country dearly – including our top credit rating and more than $1.7 trillion in corporate profits that are sheltered abroad. Political brinkmanship and paralysis have now become a form of governance and it is time for change.

Cause for Optimism

Despite the ominous assessment laid out in the HBS and ASP reports, there is a silver lining. Policymakers appear to have a “this too shall pass” attitude about the current state of paralysis that is gripping Washington. Additionally, many of the precepts identified in both reports have broad bipartisan support. The reports highlight a consensus between national security and business leaders on immigration reform, in particular high-skilled labor, infrastructure, the business climate (or commons in HBS parlance) and national debt. Responsibly harnessing America’s shale gas bonanza, which is projected to make the country energy independent by 2020 and a net exporter of oil, is perhaps the most important value driver the U.S. economy has in the near term.

|

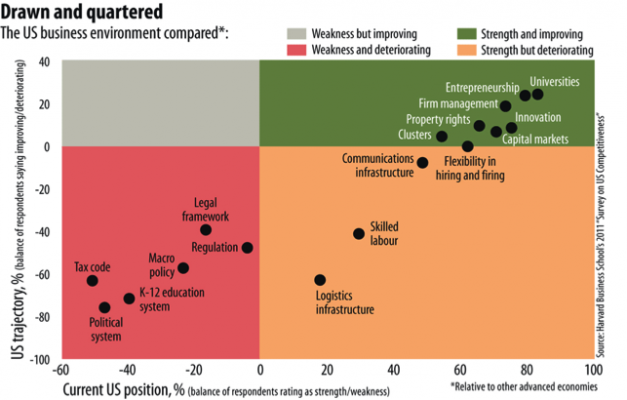

Figure 2: Strengths and weaknesses of the U.S. economy

(Source: Michael E. Porter and Jan W. Rivkin, “What Washington Must Do Now,” The World in 2013, The Economist, November 21, 2012) |

While many of America’s competitiveness challenges may be generational in nature, requiring steadfast bipartisan leadership, there is an inherent antifragility in the federated system. In short, communities, cities and states will simply move on while Washington dithers, in effect, decoupling their fortunes from those of the country as a whole. As in past times of national crisis and reinvention, the first steps towards lasting solutions start at a local level. Citizens can and should urge their elected representatives to serve them by cooperating and through compromise. The red quadrant (weakness and deteriorating) in Figure 2 clearly shows a nexus around issues that only the Federal government can tackle. Competitiveness is a politically agnostic subject that is indiscriminate in its adverse effects. Businesses can certainly do more to prevent the rich American commons from eroding and HBS’ research highlights a number of key measures to increase local and regional competitiveness. These measures include the formation of regional clusters, apprenticeship programs, and “reshoring,” among other initiatives.

A Call to Action

As the President of the HBS Club of Washington, D.C., which represents more than 3,000 area alumni, changing the tide on competitiveness is a tangible proposition. As part of a network of more than 78,000 alumni in 167 countries, all educated to make a difference in the world, I believe that harnessing our collective strength and with alumni clubs serving as an amplifier, concrete action is possible. With D.C. as a home, the four quadrants of the District stand in stark relief to one another in terms of economic development, infrastructure and the educational system – a veritable microcosm of the many challenges and opportunities facing the nation. I have called upon the local alumni network and the business community at large to help us make a difference right here in the nation’s capital.

Each year, the Club, a 501(c)3, gives scholarships to two local nonprofit leaders to attend the Strategic Perspectives in Nonprofit Management course at HBS. Additionally, we work with local partners like Compass, which was started by HBS graduates, to provide pro-bono management consulting to D.C. area schools and charitable organizations. We have also partnered with the College Success Foundation-DC, a group that is addressing systemic educational failures among the District’s inner-city communities granting the support and scholarships needed to achieve the dream of a college degree. While all of these efforts are clearly valuable, so much more can be done, including the formation of a regional competiveness council to give voice and resources to local initiatives. Building public-private partnerships, with the HBS Club serving as a bridge, can foster an exchange of ideas and an army of willing and able local alumni to make lasting change. The simple act of opening the doors of our businesses for apprentices, and the doors of our homes for mentoring, is not merely an act of altruism, but is something that is undeniably good for business and the nation.

The article was first published at http://www.hbs.edu/ on July 13, 1013

[1] Convergence is drawn from the 8 points on “What Washington must do now” an essay published by Professor Porter and Professor Rivkin in The Economist’s The World in 2013, published on November 21st, 2012 and ASP’s American Competitiveness: A Matter of National Security, written by August Cole and published on November 28th, 2012.

[2] Michael E. Porter and Jan W. Rivkin, “Prosperity at Risk,” Harvard Business School, January 2012. Report available at http://www.hbs.edu/competitiveness/survey/2012-01-12_2.html

[3] Michael E. Porter and Jan W. Rivkin, “The Looming Challenge to U.S. Competitiveness,” Harvard Business Review, March 2012

[4] Ingo Walter, “Economic Drivers of Structural Change in the Global Financial Services Industry,” Long Range Planning, Volume 42, Issues 5–6, October–December 2009, Pages 588–613

[…] U.S. Competitiveness: A Matter of National Security […]