President Trump in China. White House photo.

President Trump in China. White House photo.

US Public Diplomacy Strategy for 2018 – What’s Needed?

As 2017 comes to a close, public diplomacy at the State Department finally has a new leader with the appointment of Under Secretary Irwin Steven Goldstein. Goldstein’s appointment is welcome and needed—especially considering the lack of an official Under Secretary in that role since January—but a serious challenge lies ahead.

For Goldstein to be effective in his new position, he not only needs to have a good personal relationship with the Secretary of State, but with President Trump as well. This means access to- and policy receptiveness by these parties—and the reality of that may be unlikely.

That’s unfortunate, because effective leadership is critical now: American credibility is in danger. Preventing a complete collapse of that credibility may be impossible without making serious changes to the manner in which our great country presents itself to the world.

The bottom line is America’s leadership needs to better match the words of its rhetoric with the ideals for which this country stands: things like freedom of the press, the sanctity of America’s word and its commitments, freedom of religion (regardless of religion), and respect for our allies. America also needs to listen to the rest of the world, and use the information it learns through listening to fine tune the methods by which it pursues its objectives.

For America to improve its message abroad, several things need to be realized.

“America First” is by its nature an ineffective message amongst foreign audiences. It works at home, and America’s needs should be prioritized, but this type of rhetoric makes progress difficult by reducing the value of pre-existing relationships with America’s partners overseas. Routinely declaring American self interest in the face of friends and enemies alike is self-defeating, by devaluing the relationships and input of those we seek to influence.

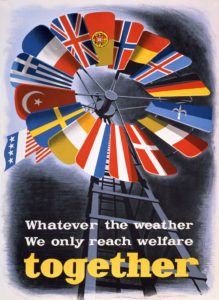

Additionally, America needs people around the world to want what it wants, without coercing them to do so. This “soft power” cannot be bludgeoned from those with whom we want to modify our relations. America should pursue its interests, and putting America first means realizing the importance of other international actors in its success and security. Messages of “togetherness” could be much more positive internationally, and help bring more of the international community on board—whether that’s to increase NATO defense spending, or to put more pressure on North Korea.

Messages of togetherness may be more effective than “America first,” as evident in this Marshall Plan poster from 1950.

If America is going to maintain leadership in the world, people abroad need to see and want America as a leader. They must see a relationship with the United States as neither adversarial nor transactional, but rather as being in their best interest. They must feel they are valued in the relationship. Simply declaring America as “the best” doesn’t make people believe that notion. The United States needs to demonstrate why it’s the best—beyond pure economics and beyond military might.

The problem is the rhetoric and actions of the United States over the course of 2017 have run directly against a positive international image. We need to stop declaring every deal we’ve made “bad.”

The president has continuously derided the Iran Deal, threatening to withdraw, while simultaneously calling on North Korea to come to the table and make a deal. Every other partner in the deal, including the inspection teams themselves, have found the deal to be working. Why would North Korea, or any other negotiating partner, give any credence that the U.S. was negotiating in good faith? If the U.S. tears up the Iran Deal, would anyone honestly trust America’s word?

Further challenging our trust abroad, we have torn up trade deals that we have negotiated for years to achieve. The president routinely derides the trade relationships the US has with its allies while visiting those countries. While visiting South Korea, Japan, Germany, and other countries, the president has complained that our trade relations with these allies is “unfair.” Though there are certainly adjustments worthy of consideration, constantly painting the U.S. as a victim of the world’s “unfair” trade practices doesn’t gain America any sympathy in the eyes of its trading partners. These deals should benefit other countries as well. Making sure that other countries benefit from trade deals with the U.S. bolsters America’s goals by increasing stability and security abroad, and reducing the demand for desperate economic (and often illegal) immigration to the U.S.

Throw the Paris Climate Accord on top of this—a deal in which the U.S. set its own commitments—and America starts to look very fickle amongst the international community.

Further denigrating our credibility amongst foreign publics are continuous attacks on legitimate news outlets in the U.S. as being “fake news.” This domestic strategy is providing fodder for autocratic regimes around the world, when America has traditionally been a proponent of press freedom. The freedom of the press within the U.S. to challenge the government is a shining beacon of American democracy, and sets an example for the rest of the world to follow.

Compounding all of these problems, there does not seem to be any urgency to supporting the State Department’s mission. Budget efficiency is not the same thing as budget effectiveness. Budget and staffing cuts don’t necessarily make an organization more efficient or effective. The question that should be asked is, “What can we do to make the State Department better able to pursue America’s interests abroad?” If the State Department becomes more efficient and streamlined, the Trump Administration should also explore the possibility of increasing or maintaining current funding levels and staffing in ways that improve America’s ability to protect and pursue its interests abroad. State needs the personnel, equipment, and financial resources to do this.

Certainly, the Trump Administration has not been alone in its difficulties with messaging abroad—and some of these difficulties have undoubtedly led to the frustration the administration expresses. For example, the U.S. has never been seen as a particularly good messenger when it comes to audiences vulnerable to extremist recruiting. Because of this, we need more credible peer-messengers and local opinion leaders to deal with the fence sitters. The State Department can help identify these messengers and quietly support them, but its true strength is preventing the conditions that would lead to even looking at the fence as an option.

Given all these problems, the U.S. government simply is not viewed as a trustworthy or reliable partner by many foreign publics at this time. It has, can, and should do better. What does this matter? If we want countries to sign up to new deals, people to support our policies, and want partners to help secure the world against countries like North Korea, we need people who will work with us. We need people around the world to see how great America is.

As the credibility of the United States and confidence in its leadership wanes amongst foreign publics, people-to-people diplomacy may be more important than ever before.

It will be incumbent upon the people of the United States to make an effort to build relationships abroad that are resilient to the volatile nature of domestic politics. America’s relationships with countries cannot be held hostage to partisan politics, changes in administrations, or the arbitrary whims of its leadership. We should build relationships that are robust, beneficial, and transcend beyond the leadership of the countries involved. This is where our budget dollars should go—connecting people, expertise, knowledge, entrepreneurship, and friendship around the world that will benefit us all in the long run.

Exchange programs need to receive an extra level of support—whether academic, scientific, professional, cultural, or even political. They should receive financial support from our government, and moral and logistical support from our people. These people-to-people public diplomacy programs often remove the government as the primary messenger, instead focusing on exposing people to each other, to culture, and to an immersive experience that few other forms of public diplomacy can match.

The world can learn a lot from America in this time, and America can learn a lot from the world.